AIC(Asian Institutional Critique)는 아시아를 방법론으로 삼아 미술 생태계를 비판적으로 사유하는 큐레토리얼 프로젝트입니다. 미술 실천안에서 정치적이고 수행적으로 제도와 범주, 그리고 공동체를 다르게 만드는 일에 관심을 가지는 아시아 창작자들을 주목합니다.

AIC의 첫 번째 주제어는 ‘방법론으로서의 아시아’입니다. 여기서 아시아란 하나의 본질이나 정체성이 아니라 지식을 구성하는 특정한 방식에 관한 문제이며, 고정된 실체가 아니라 끊임없이 지연되고 부딪히는 개념입니다. 따라서 AIC는 아시아의 의미를 단언하지 않습니다. 다만 구체적이고 특수한 사례들을 통해 잠시나마 기능하는 인식론적 틀을 만들어 봅니다. 이는 사유의 방법과 태도의 문제를 다루는 것으로, 특정한 시공간 속에서 끊임없이 재구성되는 관계와 의미를 존중하는 작은 윤리를 의미합니다.

이는 자연스럽게 AIC의 두 번째 주제어인 ‘비평성’으로 이어집니다. AIC의 비평성은 이미 구획된 제도와 미술사를 대체하기 위한 논리가 아니라, 현실에서 작동 중인 시스템의 자장을 이해하고 그 자리에서부터 비판적 상상력을 발휘하기 위한 장치입니다. 제도 비판이 지닌 미학적 정치성은 예술 창작을 위해 포기되다시피 한 부산물을 돌보는 마음가짐에서 비롯됩니다. 그러한 다정한 태도를 장착한 미술이 감각과 사고의 지형을 바꾸는 가능성을 발견합니다.

쑨거와 에이미 린

그리고

AS의 글은 ‘방법론으로서의 아시아’를 이해할 수 있는 실마리가 됩니다. 아시아를 방법론으로 삼는다는 것이 무엇을 의미하는지, 그리고 그로부터 어떤 인식의 지평이 열리고 상상력을 펼칠 수 있는지를 알려줍니다. 이는

에킨 키 찰스와

응우옌 트린 티의 영상으로 이어집니다. 두 작가는 공동체를 감각하고 기억하며, 전통과 규율, 감각의 위계를 다시 구성하는 서로 다른 방식의 돌봄의 사유를 보여줍니다.

게시야다 시레가르는 인도네시아의 굿키친의 사례를 바탕으로, 협업 노동을 의미하는 커르자 바크티에서 불가피하게 발생하는 소진의 감정에 대해 말하며, ‘그럼에도 불구하고’ 함께 만들기를 지속하게 하는 힘에 관해 고찰합니다. 이처럼 AIC가 호출하는 아시아란 스스로의 위치에서부터 공동에 관한 지식을 발명하는 감각적이고 윤리적인 현장입니다.

이 관점은

유간타르와

한옥희에게서 다시 한번 구체화됩니다. 인도의 실험영화 집단 유간타르는 여성 미술가의 비가시성과 성차별적인 제도의 처우에 어떻게 대응할 것인가 질문하며 공동으로 미술을 제작했습니다. 남성중심주의적인 제도에 균열을 내는 언어와 방법론은 한옥희의 용감한 실험성과 맞닿습니다. 이 흐름 속에서 필리핀의 카시불란을 이끌었던

이멜다 카지페 엔다야와

이솜이의 대화를 독해할 수 있습니다. 신뢰와 애정은 현재를 살아가는 여성들에게도 그 유효성을 여전히 실험, 증명하고 싶은 영역일 것입니다. 그 바람은

무니페리에게로 이어집니다. 그는 칠선녀를 찾아 떠난 홍콩 답사기를 통해 쉬이 가시화되지 않지만 우리 곁에 실재하며 잔존하는 믿음에 관한 깨달음을 들려줍니다. 이는

쉔신의 영상에서 여러 겹의 소리와 이미지를 통해 끊임없이 어긋나고 겹쳐지는 감각으로 은유됩니다.

이렇게 모아진 생각들은 미술이 만들어지는 과정을 하나의 상호 배움으로 전제하며, 관계 맺음을 통해 미학적이고도 정치적인 실천을 할 수 있는가에 관한 질문으로 귀결됩니다.

사이먼 순은 선택과 배제라는 큐레토리얼 지식 체계에 관해 성찰하며, 큐레토리얼 진정성이 발현될 순간을 기대합니다. 그 기대는 작가들과 시간을 나누며 쌓인 존중의 마음, 그리고 전시를 결과가 아닌 하나의 과정으로 상상하는 방식으로 비롯된

조이 버트의 우정 실천과 맞닿아 있습니다.

유승아는 AIC를 기획하는 과정에서 참고한 이론가, 작가, 미술 동료의 사유들을 적극적으로 호명하며, 인용으로 연결되는 관계 맺기를 제안합니다. 그 안에 삽입된

이빈소연의 영상은 이 방법론에 응답해, 차학경을 받아쓰기하며 매듭처럼 연결되어 있는 미술적 우정을 보여줍니다. 우정의 방법론은 각자의 경험을 나누고 들으며 서로를 통해 비추어 지고 다시 포개어지는

아프사×다브라에게로 확장됩니다.

이러한 사유들의 다발은

OTP를 통해 그래픽 언어로 옮겨졌습니다. 변환되며 연쇄되는 심볼은 방법론으로서의 아시아를 상징합니다. 나타남과 사라짐이 깜빡이며 이어지는 가운데, 어디로 도달할 지 모르는 신비한 여정을 암시합니다. 구동된 웹사이트는 마주침과 동행, 대화를 서사화하는 장치로, 수직 수평 운동처럼 느껴지지만 마치 구체 안에 있는 듯 합니다.

그러니 멀고도 아득히 느껴지는 사람들의 이야기들, 혼연함으로 가득찬 공간 가운데, 이 모든 상황을 단번에 이해할 것 같은 순간을 홀연히 경험하게 된다면, 그것은 우연이 아니라 정합적인 일일 것입니다.

AIC(Asian Institutional Critique) is a curatorial project that critically examines art institutions through Asia as a methodology. Acknowledging that we have thus far failed to care attentively for the agents involved in artworks and institutional systems, AIC focuses on Asian practitioners whose artistic practices pursue political and performative approaches to reconfigure institutions, categories, and communities in alternative ways.

The first key theme of AIC is “Asia as Methodology.” Here, Asia is not an essence or a fixed identity, but a question of the specific ways in which knowledge is constructed. It is a concept that is continuously deferred and constantly in tension. Therefore, AIC does not seek to assign a single, definitive meaning to Asia. Instead, it seeks to create an epistemological framework that can function, however briefly, through concrete and specific cases. This approach reflects an attitude: a modest ethics that honors relationships and meanings that are continuously reconfigured within particular times and places.

This naturally leads to AIC’s second key theme: criticality. The criticality AIC pursues is not a logic aimed at replacing existing institutions or established art histories. Rather, it is a tool for understanding the forces at play within systems already in operation, and for cultivating critical imagination from within those conditions. The aesthetic and political power of institutional critique emerges from a willingness to care for the by-products often overlooked or abandoned in the process of artistic creation. From this attentive and compassionate stance, we can uncover the potential for art to transform the landscape of perception and thought.

The writings of

Sun Ge & Aimee Linand

ASprovide insights into what it means to approach Asia as a methodology. They reveal the epistemic horizons that open up and the forms of imagination that become possible when Asia is engaged in this way. This inquiry continues in the videos by

Ekin Kee Charlesand

Nguyễn Trinh Thi, both of whom explore care-based thinking rooted in the communities they inhabit. Drawing on the example of Gudkitchen in Indonesia,

Gesyada Siregarreflects on the emotional exhaustion that inevitably accompanies collaborative labor—Kerja Bakti—and considers the sustaining forces that enable people to keep creating together despite it all. In this sense, the “Asia” invoked by

AICfunctions as a sensory and ethical site, where knowledge of the communal is actively invented from one's own situated perspective.

This perspective is further articulated in the works of

Yugantarand

Han Okhi. The Indian experimental film collective Yugantar created art collaboratively, asking how to respond to the invisibility of women artists and the discriminatory practices embedded in patriarchal institutions. Their language and methods—cracking open male-dominated systems—resonate with the bold experimental spirit explored by Han Okhi. Along this trajectory, we can also consider the conversation between

Imelda Cajipe Endaya, who led the Philippine women's collective Kasibulan, and

Somi Lee. The trust and affection among women that Kasibulan embodied remains a field that contemporary women continue to explore, test, and affirm for its ongoing relevance. This exploration extends to

Mooni Perry, who, through her account of traveling in Hong Kong in search of the "Seven Fairies," reflects on beliefs that, though not easily visible, persist quietly alongside us. A similar sensibility is expressed in

Shen Xin's video, where layers of sound and image metaphorically convey an experience that continually slips away, never fully arriving.

These reflections are grounded in the premise that the process of making art can be understood as a form of mutual learning, raising a central question: Can aesthetic and political practices be cultivated through the act of forming relationships?

Simon Soonreflects on professional ethics through the curatorial mechanisms of selection and exclusion, anticipating the moment when curatorial sincerity might fully manifest. This anticipation finds resonance in

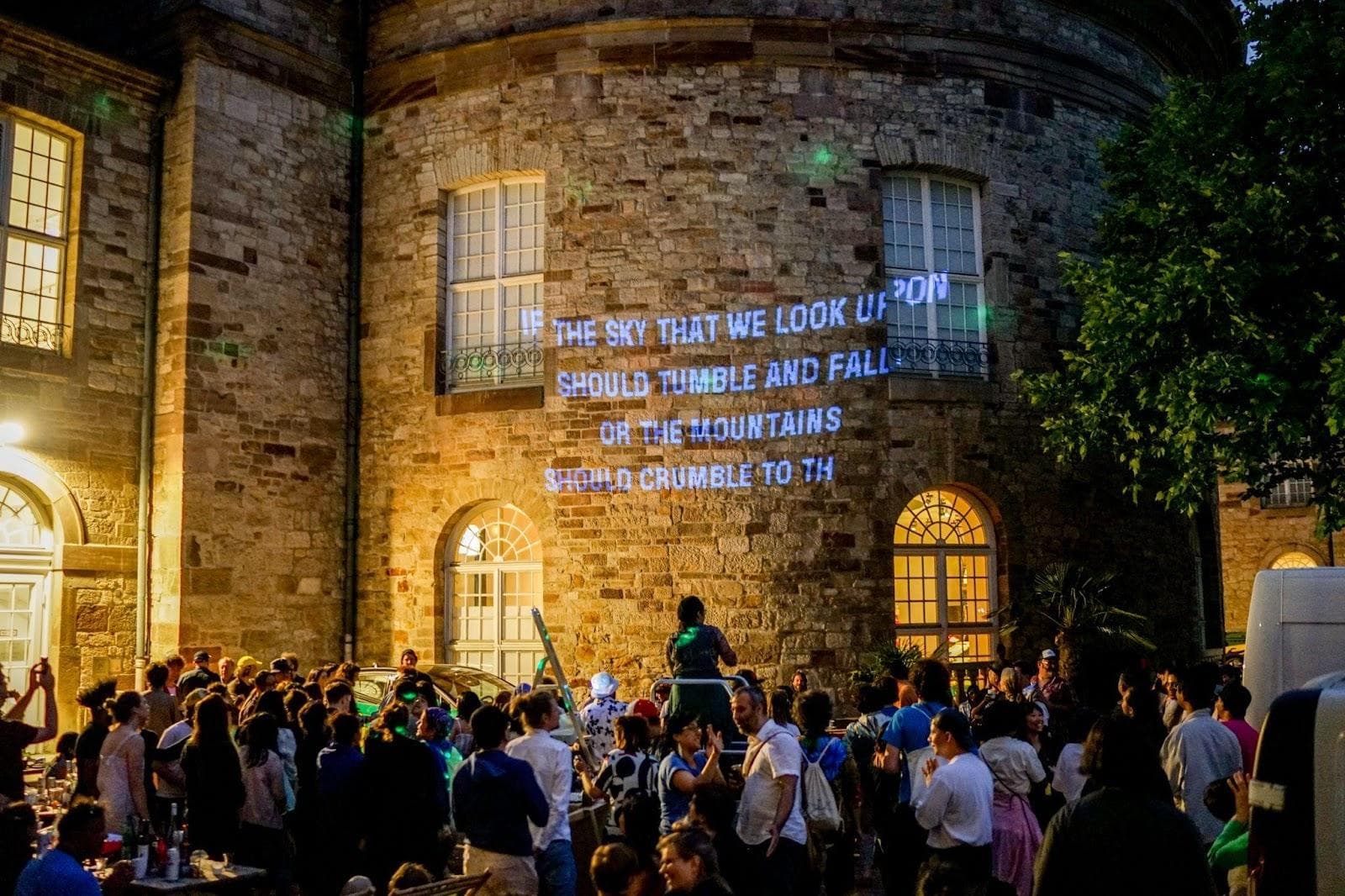

Zoe Butt's practice of friendship—rooted in respect, in spending time with artists, and in imagining exhibitions not as fixed outcomes but as ongoing processes.

Seunga Youactively invokes the thinkers, artists, and colleagues whose ideas shaped the making of

AIC, proposing citation-as-connection as a practice in itself. Responding to this methodology,

Leebin Soyeon's video illustrates an artistic friendship woven like a knot, created through the act of transcribing Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. This approach to friendship extends further in the video by

AFSAR×DAVRA, where personal experiences are shared, listened to, and reflected upon, layering through one another to create a collective, resonant dialogue.

These clusters of ideas were translated into a graphic language through

OTP. The continually transforming and cascading symbols evoke Asia-as-method, a methodology formed through layers, overlaps, and slippages. The activated website functions as a device that narrativizes encounters, companionship, and conversation. Though its motion feels vertical and horizontal, it also gives the impression of being inside a sphere. This metaphorically suggests a belief that we are continuously linked to one another, slipping and connecting in an ongoing flow. Therefore, if—amid these stories of people who seem distant and almost unreachable, within this space filled with fluid entanglements—you suddenly experience a moment where everything appears to come into understanding, it would not be coincidental, but rather entirely coherent.

원리로서의 아시아 Asia as Principle

I. 아시아란 무엇인가?

에이미 린아시아란 무엇을 의미하나요? 단지 지리적 개념을 넘어서는 의미가 있나요?

쑨거 물론입니다. 아시아는 단순히 하나의 공간적 개념으로 한정되지 않습니다. 다시 말해, 단순한 지리적 구획을 넘어, 정치적·역사적·지리적 의미가 복합적으로 교차하는 개념이라고 생각합니다. 학계에는 ‘정치·역사 지리학(political historical geography)’이라는 연구 분야가 있는데, 이 영역에서는 다양한 정치적·문화적·역사적 문제들이 그것이 발생한 장소의 맥락 속에서 논의됩니다. 아시아 역시 그러한 복합적 개념으로 이해될 수 있지만, 저는 여기에 자주 간과되는 또 하나의 중요한, 대안적인 기능이 있다고 생각합니다. 그것은 바로 후도(風土, fūdo) — 즉, 지역의 자연과 인간이 함께 만들어내는 감각적이고 정신적인 풍토의 특성입니다.

에이미 린후도(fūdo)란 무엇인가요?

쑨거 후도는 특정 지역이나 지리적 공간이 지닌 자연 지리적 특성을 뜻합니다. 이러한 특성이 사회적 활동과 결합되어 인간의 정신적 삶 속에 스며들 때, 우리는 그것을 후도라고 부릅니다. (후도(Fūdo, Fengtu)는 일본 철학자 와쓰지 테츠로(和辻哲郎, 1889–1960)가 저서 『후도: 인간학적 고찰』(1935)에서 제시한 개념으로, 문자 그대로 ‘바람과 땅’을 뜻하며 특정 지역의 자연환경을 가리킵니다) 따라서 아시아라는 개념 역시 인간의 활동을 통해 형성된 정치적·역사적·정신적 문화가 자리하는 하나의 자연지리적 공간으로 이해할 수 있습니다. 인문학이 만들어내는 다양한 정신적 산물들은 언제나 이러한 특정한 공간의 맥락 속에서 논의됩니다.

에이미 린‘아시아’라는 이름은 본래 외부인들이 특정 지리적 공간을 가리키기 위해 사용한 것이었습니다. 그렇다면 ‘아시아’, 혹은 ‘아시아라는 개념’은 이 장소에서 살아가는 사람들에게는 어떤 의미일까요?

쑨거 근대 이전까지 ‘아시아’라는 개념은 주관적 정체성을 내포하지 않았지만, 20세기에 들어 그 의미가 달라졌습니다. 십자군 전쟁 당시 이 용어가 아시아 소아시아(Anatolia)만을 의미했던 시기부터 20세기 초 유럽이 세계를 식민지화하던 시기에 이르기까지, 서구의 아시아 담론은 일관되게 아시아를 유럽의 ‘타자(other)’로 상정했습니다. 이슬람 세계가 전성기를 누리던 시기에는 그 ‘타자’가 결코 만만치 않은 존재였으나, 근대에 들어서는 비교의 대상으로 전환되어 유럽 문화의 우월성을 입증하는 근거가 되었습니다. 제2차 세계대전이 끝날 때까지 유럽의 이데올로기는 아시아를 대등한 주체로, 혹은 상호적으로 이해할 수 있는 대상으로 인정하지 않았습니다. 그러한 관계가 성립한다 하더라도 그것은 현실이라기보다 가능성의 차원에 머물렀습니다. 오늘날까지도 유럽 내부에서 아시아를 동등한 대화의 상대로 인식하는 관점은 여전히 중심이 아닌 주변부에 머물러 있습니다.

아시아의 관점에서 보면, 아시아라는 개념이 정치적 상징으로 전환되는, 보다 광범위한 흐름은 제2차 세계대전 이후에 나타났습니다. 이 시점부터 아시아는 더 이상 서구가 만든 개념으로만 규정될 수 없게 되었습니다. 이러한 상징의 전환은 1955년 반둥 회의(아프리카·아시아 국가들이 참여한 비동맹 운동의 전신 회의)에서 두드러졌습니다. 이는 어디까지나 아시아 담론이 변화해 온 과정 중 하나의 국면으로 볼 수 있을 것입니다. 넓은 역사적 흐름에서 보면, 20세기에 들어 일부 아시아 사회에서 ‘아시아’라는 개념이 정치적 주체성을 상징하는 기호로 사용되기 시작하면서, 아시아 담론은 본격적으로 전개되었습니다. 이러한 정치적 주체성의 형성은 일본에서 처음 나타났습니다. 일본에서의 아시아주의는 1904–1905년 러일전쟁을 계기로 절정에 달했습니다. 당시 일본인들은 이 전쟁을 인종 간의 전쟁으로 인식했고, 황인종이 백인종을 이긴 사건으로 해석했습니다. 중국 혁명가 쑨원(Sun Yat-sen)은 수에즈 운하를 여행하던 중 한 아랍인이 자신에게 일본인이냐고 물었던 경험을 회상합니다. 당시 아랍인들은 동아시아와의 연대감을 잘 표현하지 않았지만, 러일전쟁은 그들에게 동아시아를 ‘황인종 세계의 일부’로 인식하게 만드는 중요한 계기가 되었습니다. 다만 일본식 아시아주의가 전쟁과 함께 확산되었고, 그 전쟁 방식이 유럽의 식민주의를 답습했다는 점은 비극적입니다. 결국 일본의 아시아주의는 진정한 아시아주의가 아니라 유럽주의의 변형된 형태였습니다. 이러한 유럽주의는 제2차 세계대전과 일본의 동아시아·동남아시아 침략에서 가장 전형적으로 드러났습니다. 일본의 식민지 지배와 전쟁 수행 방식은 초기 유럽 식민주의의 틀을 거의 그대로 답습한 것이었습니다.

따라서 아시아주의가 아시아에 존재한다고 말할 수 있다면, 그것은 단일한 형태가 아니라 여러 얼굴을 가진 복합적인 사상이며, 그 사이에는 긴장과 모순이 공존합니다. 가치 판단을 배제하고 말하자면, 19세기 후반부터 아시아의 여러 지역에서 서구가 부여한 ‘타자’적 문화 상징을 벗어나 자신들의 정체성을 드러내려는 다양한 움직임이 나타나기 시작했습니다. 따라서 서구가 정의한 ‘아시아’의 개념은 20세기 이후 아시아인들이 ‘아시아’를 주체적으로 사용하게 된 맥락을 충분히 해명할 수 없습니다.

에이미 린그렇다면 제2차 세계대전 이후, ‘아시아’라는 개념의 의미에는 어떤 변화가 있었을까요?

쑨거 제2차 세계대전 이후 ‘아시아’라는 개념은 반둥 회의에서 아프리카와 아시아, 즉 두 대륙의 탈식민 독립운동과 긴밀히 연결되며 사용되었습니다. 이 시점에서 아시아 정체성의 핵심은 국가 단위의 독립과 해방 운동에 있었습니다. 1950년대 아시아가 부상하는 과정에서 정치 단위로서 아시아의 가장 중요한 의미는 정치적 주체성이었습니다. 일본을 제외한 대부분의 아시아 지역이 직간접적인 식민 지배를 경험했기에, 이러한 차별과 굴욕의 역사 속에서 아시아는 1950년대에 강력한 연대 의식을 형성하게 되었습니다. 아시아는 유럽과 달리 하나의 종교로 통합될 수 없는 지역입니다. 아시아에는 최소 세 가지 주요 문명이 존재하고, 그 안에는 쉽게 통합될 수 없는 여러 종교 전통이 공존합니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 반둥 회의는 1950년대 아시아 전역에 ‘아시아’라는 개념을 적극적으로 확산시킨 연대와 통합의 상징적 사건이었습니다. 이후 각국이 독립과 주권을 획득하면서 아시아의 의미와 그 내부의 관계 역시 새로운 방향으로 변화하기 시작했습니다.

에이미 린 대략 언제쯤부터 변화가 일어난 건가요?

쑨거 냉전 체제가 해체되기 시작하면서 본격화되었다고 생각합니다. 아시아는 1970년대에 들어서면서 점차 분열되기 시작했는데, 당시 대륙 전체가 직면했던 가장 큰 과제는 바로 ‘어떻게 근대화를 달성할 것인가’ 하는 발전의 문제였습니다. 그 결과 아시아와 서구 사이에는 다양한 형태의 대화와 교류, 협력이 이루어졌습니다. 그러나 그와 동시에, 1970년대 이후에는 눈에 보이지 않는 새로운 형태의 식민주의가 시작되었다고도 할 수 있습니다. 1990년대 초 베를린 장벽이 붕괴된 이후, 아시아는 ‘새로운 국제적 연대를 어떻게 구축할 것인가’라는 문제에 직면했습니다. 상하이 협력기구나 브릭스(BRICS)와 같은 새로운 연대체들은 아시아가 국제 관계 속에서 자신을 다시 정의하고 재편해하는 상징체라 할 수 있습니다. 하지만 이러한 상황 속에서 우리는, 아시아가 여전히 지리적 차원에서 자신의 정체성을 자율적으로 강조하거나 독립적인 단위로서 행동하기 어려운 상태에 놓여 있음을 보게 됩니다. 예를 들어, 동북아시아의 6자회담은 아시아에게 매우 중요한 사안이지만, 그 협상에 두 개의 비(非)아시아 국가 즉, 러시아와 미국이 개입했지만, 그 사실을 낯설게 느끼지 않았습니다. 제2차 세계대전을 거치며 미국은 아시아, 특히 동아시아에서 압도적인 영향력을 행사하기 시작했습니다. 이런 맥락에서 어떤 이들은 ‘아시아는 여전히 구체적인 현실로 자리 잡지 못했다’고 말합니다. 지리적 관점에서 보더라도, 아시아는 여전히 다른 지역의 수많은 요구와 영향력으로부터 벗어나기 어렵습니다. 결국 1950년대 반둥 회의로 상징되었던 아시아의 연대는 오늘날 사실상 해체된 상태에 놓여 있다고 할 수 있습니다.

II. 원리로서의 아시아

에이미 린 그렇다면 아시아는 지리적 공간을 바탕으로 한 통합에 이르지는 못한 것이군요.

쑨거맞습니다. 하지만 우리가 처음 논의했던 것을 떠올려 보면, 아시아는 단순한 지리적 개념이 아닙니다. 아시아는 정치적·역사적·정신적 문화를 아우르는 집합체이기도 합니다. 그것은 사람들의 정신적 활동을, 그리고 사회적·예술적 활동이 지닌 후도(fūdo)적 성격을 상징합니다. 그런 의미에서 저는 오늘날 우리가 아시아를 일련의 원리로 사유하며, 논의를 재구성하고 다시 서술할 수 있는 단계에 이르렀다고 생각합니다.

에이미 린 당신은 이전에 ‘아시아는 어떻게 의미를 갖는가?’라는 질문에 대해 글을 쓴 적이 있는 것으로 알고 있어요. 그런데 ‘원리로서의 아시아’라고 할 때는 꽤 새로운 개념처럼 들립니다.

쑨거그렇습니다. 저 역시 이 단계에 이른 것은 비교적 최근의 일입니다. 제 생각에 현재의 아시아 담론은 여전히 핵심에서 벗어나 있습니다. 아시아가 고유한 원리를 갖고 있지 않다면, 그것은 서구 담론의 틀 속에서 단지 분석의 재료로 소비될 뿐일 것입니다. 지금까지 아시아는 서구 학계와 중국 학계 모두에서 그렇게 다루어져 왔습니다. 하지만 이제는 아시아적 원리를 스스로 만들어내야 한다고 저는 믿습니다. 그러나 아시아적 원리를 만든다는 것은 아시아인들만을 위한 일이 아닙니다. 그것은 인류 전체를 위한 역사적 책임이라고 생각합니다. 아시아적 원리란 유럽적, 아프리카적, 라틴아메리카적 원리에 상응하는 것입니다. 그러나 이것을 논하는 일은 서구에 맞서거나 그것을 대체하기 위한 지적 시도가 아닙니다.

에이미 린 원리로서의 아시아를 논하기에 앞서 묻고 싶습니다. 예술과 문화가 아시아의 정체성, 혹은 아시아라는 관념을 형성하는 데에 어떤 역할을 하고 있습니까?

쑨거 예술과 문화는 정신적 에너지에 형태를 부여하는 행위입니다. 인간의 정신적 활동은 외부로 드러나기 위해 반드시 어떤 형태를 가져야 하죠. 예술은 관찰을 통해 얻은 감각적 경험을 시각적, 청각적 언어로 번역함으로써 정보를 전달합니다. 하지만 지금까지 제가 접해온 동아시아의 미술, 연극, 영화와 같은 예술의 주류는 전반적으로 서구화되어 있다고 생각합니다. 그 안에서 드러나는 ‘아시아적 특수성’은 아직 충분하지 않습니다.

에이미 린 즉, 그 근거에는 이른바 아시아적 주체성에 대한 자각이 부족하고, 무의식적으로 서구의 방법이나 관점을 차용하고 있다는 뜻인가요?

쑨거 맞습니다. 대표적인 예가 장이모우(Zhang Yimou)입니다. 그의 영화 속에 나타나는 이른바 ‘중국적 표현’은 사실 할리우드의 기대와 요구를 충족시키기 위한 의도된 연출입니다. 물론 장이모우처럼 표피적인 접근을 넘어 보다 주체적으로 아시아적 요소를 탐구하려는 예술가들도 있습니다. 그러나 이들, 그리고 큐레이터들까지도 기본적으로 서구 중심의 관점을 바탕에 두고 있습니다. 예를 들어 오늘날 동시대 예술가나 큐레이터의 사고 속에는 ‘근대성’이라는 관념이 깊게 자리하고 있습니다. 그들에게 근대성에 대해 발언할 기회를 주지 않으면 자신이 맡은 역할을 다하지 못한다고 느낍니다. 이는 오늘날 분명히 존재하는 하나의 흐름이며, 정치·경제·문화 전반에 걸쳐 서구로부터 스며든 결과이므로 부정할 필요는 없습니다. 그러나 그와 동시에 아시아적 요소가 서서히 자라나고 있는 주변부의 문화와 예술이 있습니다. 이들은 아직 성장의 과정에 있으며 세심한 양육이 필요합니다. 하지만 아시아의 지식인들은 여전히 그 지점에 충분히 도달하지 못하고 있는 듯합니다. 과정이 필요합니다.

에이미 린 말씀하신 문화 활동의 예를 구체적으로 들어주실 수 있나요?

쑨거일본의 극작가 사쿠라이 다이조(Sakurai Daizo)의 텐트 극장(Tent Theatre)을 그 예로 들 수 있어요. 그의 공연은 일본의 평범한 서민층, 특히 하층 계급 사람들의 삶을 소재로 삼으며, 매우 일본적인 정서를 담고 있습니다. 사쿠라이는 탁월한 상상력을 지닌 예술가이지만, 그의 작품 세계를 온전히 이해할 수 있는 지식인의 수는 아직 많지 않은 듯해요. 그럼에도 그의 공연은 동아시아 전역에서 주목을 받고 있으며, 특히 젊은 지식인들 사이에서는 그 형식의 새로움 덕분에 높은 관심과 호응을 얻고 있습니다. 다만, 그가 담고 있는 아시아적 요소들은 앞으로 더 깊이 있고 풍부하게 발전해 나갈 필요가 있다고 생각합니다. 또 다른 예로, 한국 광주에서의 판화 활동과, 오키나와의 사진 활동을 들 수 있습니다. 특히 오키나와 미야코 제도에서는 매년 2월 열리는 제의를 기록하는 사진작가가 있는데, 그는 지역의 전통적인 생활 양식을 매우 섬세하게 포착합니다. 그러나 서구의 개념이나 해석에 기대지 않는 진정한 토착적 예술과 문학 활동은 여전히 널리 알려지거나 공유되기 어렵습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이러한 예술적 원천들은 강한 생명력을 지니고 있어 쉽게 사라지지 않을 것입니다.

에이미 린 어쩌면 그 이유는 현대 미술을 인정하고 유통하는 메커니즘 안에 있을지도 모릅니다. 결국 그 체계 속에 있는 이들은 이러한 예술을 제대로 보고 이해할 역량이 부족하기 때문입니다.

쑨거 이 문제는 조금 더 시간과 성찰이 필요한 사안이라고 생각합니다. 나아가 이는 단지 아시아인들만의 과제로 국한될 수 없는 문제이기도 합니다. 오늘날 서구 지식인의 지위와 역할, 더 나아가 서구 세계 전체의 위상이 변화하고 있으며, 그들이 아시아를 바라보는 시각 또한 점차 달라지고 있습니다. 진정한 지적 욕망을 가진 사람이라면, 그가 아시아인이든 서구인이든, ‘근대성’이나 ‘탈근대성’이라는 기존 담론만으로는 더 이상 만족하지 않을 것이라고 생각합니다. 우리의 삶은 그보다 훨씬 더 다층적이고 풍요롭기 때문입니다. 언젠가 모든 이의 경험이 보다 새롭고 깊어지는 날이 올 것이라고 믿습니다. 그런 점에서 예술과 문화는 매우 중요한 역할을 수행할 수 있는 잠재력을 지니고 있지만, 지금까지는 그 가능성을 충분히 실현하지 못했다고 생각합니다.

에이미 린 일부 서구인들은 언어 장벽 때문에 서구 사람들이 아시아 정체성을 깊고 다면적으로 이해하지 못하고, 단지 겉으로 드러나는 문화적 특징에만 의존한다고 말합니다. 그 결과, 다른 문화를 형식적으로 상상할 수밖에 없다는 것이지요. 이 의견에 대해 어떻게 생각하시나요?

쑨거 분명 하나의 요인은 될 수 있지만, 그것만으로 모든 것을 설명할 수는 없습니다. 아시아에 대한 서구의 이해 부족은 어떤 면에서는 지나친 서구 중심주의에서 비롯된 것이며, 이제 막 변화의 조짐이 보이기 시작했습니다. 서구인들이 이러한 질문을 하기 시작했다는 사실은 이미 그 문제를 자각하기 시작했다는 신호입니다. 그럼에도 여전히 대부분의 서유럽과 북미의 지식인들은 아시아에 깊은 관심을 두지 않고 있습니다. 그 이유가 단순히 언어의 장벽 때문인 것은 분명 아닙니다.

에이미 린 그렇다면 그것은 그들 자신이 속한 문화에 대한 일종의 고립주의라고 볼 수 있을까요?

쑨거 이는 최근 정치와 경제의 역사적 흐름과도 밀접하게 연결되어 있습니다. 서구는 오랫동안 유리한 위치에서 세계를 지배해왔습니다. 문화는 각기 고유한 특성을 지니고 있지만, 정치와 경제로부터 완전히 분리될 수는 없습니다. 아시아에 대해 진정한 인식과 감수성을 지닌 서구의 문화인들은 지금도 여전히 소수에 머물러 있습니다.

에이미 린 정말 드문 경우군요.

쑨거 그렇지만 저는 몇 가지 예외가 존재한다고 생각합니다. 예를 들어 중국 문제를 논할 때, 서유럽과 북미의 지식인들은 먼저 근대성, 탈근대성, 합리성, 개인의 권리, 과학주의, 진화론 등 몇 가지 개념적 틀을 제시하곤 합니다. 이러한 틀은 근대 유럽의 견고한 문화 구조를 이루는 기본 요소이며, 서구의 지식인들은 이 체계 안에서 그것들을 자연스럽고 보편적인 것으로 인식하도록 교육받아 왔습니다. 그런데 문제점은, 이러한 전통적 사고 체계를 공유하지 않거나 부분적으로만 수용한 동양과 마주했을 때 그들이 어떤 태도를 보이느냐는 점입니다. 제가 접한 대부분의 서구 지식인들은 낯선 경험을 마주하면 그것을 자신이 익숙한 틀 안에 억지로 끼워 맞추려 하고, 주저하면서도 그 틀로 해석하려 애쓰는 모습을 보였습니다.

에이미 린 그렇게 보면 ‘원리로서의 아시아’ 필요성이 명확해집니다. 서구 지식인들에게도 그것은 거대한 도전이자, 매우 어려운 과제이기 때문입니다.

쑨거 맞습니다. ‘원리로서의 아시아’는 단순한 구호가 아닙니다. 그것은 우리가 기존의 보편 개념을 새롭게 정의해야함을 뜻합니다. 우리는 다음과 같은 관점에서 출발해야 합니다. 즉, 모든 지적·정신적 활동은 고유하며, 다시 말해 후도에 의해 형성된다는 것입니다. 즉, 유럽이나 북미에서 얻은 부분적인 경험을 다른 지역에 적용하면서 그것을 인류 전체의 보편적 경험으로 간주할 수는 없습니다. 이런 접근은 처음부터 경계해야 합니다. 바로 이것이 ‘원리로서의 아시아’가 우리 인류에게 던지는 과제입니다. 오늘날 아시아를 여전히 유럽적 원리의 시각으로 바라본다면, 우리는 이른바 보편적 상상력을 동원해 아시아를 해석하게 됩니다. 그 결과 아시아 속에서 근대성을 찾고, 과학적 합리성을 추구하려는 태도로 이어집니다. 이런 태도는 서구인들에게만 나타나는 것이 아니라, 아시아인들 역시 무의식적으로 동일한 방식을 따르고 있습니다.

에이미 린 그것은 결국 우리가 받은 교육과 학문적 훈련을 통해 사고의 방식이 이미 서구화되었기 때문이겠지요. 하지만 우리의 삶과 신체적·감각적 경험은 이러한 정신적 체계를 넘어섭니다.

쑨거 이러한 교육적 배경을 가진 사람들은 다양한 아시아 사회에서 일어나는 변화를 해석하는 데 어려움을 겪습니다. 예를 들어, 현재 중국 사회에서 나타나는 높은 이동성, 더 구체적으로는 대규모 이주 노동 현상을 우리는 어떻게 이해해야 할까요? 중요한 것은 각 사회의 존재를 정당화하는 것이 아니라, 그것을 이해하려는 일입니다. 이는 긍정이나 부정의 문제가 아니라, 이해의 문제이자 지적 탐구의 영역입니다. 저는 예술을 창작하는 사람은 아니지만, 지적·역사적 관점에서 보았을 때 이 문제는 매우 시급합니다. 바로 이것이 우리가 아시아적 원리에 대해 논의해야 하는 이유입니다. 제 생각에 아시아적 원리를 가장 단순하게 요약하면, 그것은 다양한 물리적 현상의 공존을 전제로 한 보편주의라고 할 수 있습니다.

에이미 린 물리적 현상이란 말씀은, 앞서 말씀하신 후도를 의미하나요?

쑨거네 맞습니다.

III. 아시아 미술을 위한 전제

에이미 린학문적 관점에서 볼 때, ‘아시아 미술’이라는 것이 과연 존재한다고 할 수 있을까요? 그렇다면 그 미술의 이른바 ‘아시아성’은 무엇으로 이루어져 있을까요?

쑨거 아주 중요한 질문이라고 생각합니다. 우선 저는 아시아 미술의 존재가 단순히 가능하다는 수준을 넘어, 반드시 필요하다고 생각합니다. 다만 아시아 미술은 본질적으로 다양성을 전제로 합니다. 그렇기 때문에 아시아 미술에 대해 이야기할 때 가장 먼저 전제되어야 할 것은, 그것이 특정한 대표성을 갖지 않는다는 점입니다. 서구 미술은 비교적 쉽게 대표적인 학파나 경향을 열거할 수 있지만, 아시아 미술은 그렇지 않습니다. 그리고 그 차이가 바로 아시아 미술의 특징입니다. 아시아 미술에는 전체를 아우르는 근본적이거나 일차적인 기준이 존재하지 않습니다.

에이미 린아시아 미술에는 그것을 하나로 묶는 공통된 특징이 없는 것이군요.

쑨거지난 한두 세기 동안 우리는 서구의 강력한 영향 아래에서, 어떤 분야를 논할 때 대표자나 중심을 상정하고 그에 대해 이야기하는 방식에 익숙해졌습니다. 하지만 이제 필요한 것은 하나의 중심이 아닌, 다원성을 인식하고 논의하는 습관을 갖추는 일입니다. 이것이 바로 아시아 미술을 논하기 위한 기본 전제입니다. 왜냐하면 아시아 미술은 본질적으로 통합될 수 없는, 다양한 특수성들로 이루어져 있기 때문입니다. 중국 철학자 천쟈잉(Chen Jiaying)이 제안한 ‘특수(the particular)’라는 개념은 바로 이러한 맥락을 잘 보여줍니다. 그는 개인과 그 특성이 결합된 고유한 양상에 주목했습니다. 저는 아시아 미술이 무수히 많은 이러한 ‘특수’들로 이루어져 있다고 생각합니다. 그러나 그것은 단순히 이것저것을 모아놓은 집합이 아닙니다. 만약 그렇게 단순한 것이라면, 아시아 미술은 존재하지 않을 것입니다. 중요한 것은 이 수많은 특수들 사이에 존재하는 관계이며, 우리는 이 관계를 아시아적 원리에 따라 이해해야 합니다. 그 관계들의 의미는 무엇일까요? 다양한 특수들은 절대로 동일하지 않으며, 서로 맞닿는 방식 또한 일률적이지 않습니다. 이러한 특수들 간의 관계를 설정하는 과정에서, 좋고 나쁨이라는 기준은 존재하지 않습니다. 이러한 사고방식은 유럽적 원리와는 다른 것입니다. 아시아 미술은 특수들 간의 관계를 상호 이해, 자기 해방, 그리고 개인의 초월을 통해 구성하려는 시도가 있을 때 비로소 형태를 갖춥니다. 그렇기 때문에 우리는 유럽의 근대성과 탈근대성을 기준으로 아시아 미술을 해석하는 관행에서 벗어날 필요가 있습니다. 현재 우리의 감상 습관은 여전히 우리 자신의 문화를 영어로 번역한 뒤, 그 번역을 통해 타 문화를 이해하는 방식에 머물러 있습니다.

에이미 린아시아에 대한 이러한 관념 속에는 서구 세계나 그 이론에 충돌하거나 대립하는 요소가 있나요?

쑨거그렇습니다. 하지만 저는 그 점이 그렇게 본질적인 문제라고는 생각하지 않습니다. 지금까지는 서구의 방법론에 저항하는 것이 어느 정도 필요했지만, 무언가에 맞서는 순간 우리는 곧 그 반대항 안에 갇히게 됩니다.

에이미 린결국 스스로를 제한하게 되는 셈이군요.

쑨거맞습니다. 이는 지식 생산의 과도기적 단계이며, 본질적으로 건설적인 방식은 아닙니다. 예를 들어, 탈근대성(post-modernity)은 근대성(modernity)에 의해 제한되기 때문에 완전히 자유로울 수 없습니다. 아시아 역시 서구에 의해 일정하게 제약받고 있습니다. 이것은 피할 수 없는 역사적 조건입니다. 만약 그런 한계 속에서 진정한 자기 해방을 이루고자 한다면, 단순한 비판만으로는 부족합니다. 우리는 서구를 부정하는 것이 아니라, 상대화해야 합니다. 핵심은 서구가 아시아에 끼친 영향까지 포함해 스스로의 이해와 체계를 구축하는 것입니다. 단순히 서구를 부정하고 반대하는 것은 아무런 건설적 기능을 가지지 않습니다. 아시아적 사유와 문화를 확립하려면 구조적 구축이 필요합니다. 지금까지 동양의 지식인들이 취해온 두 가지 방식은 서구를 비판하거나 개혁하려는 접근이었는데, 이 두 방향은 모두 의미가 있지만 동시에 서구의 틀과 밀접히 연결되어 있습니다. 저는 이러한 방식들이 과도기적인 단계라고 봅니다. 우리가 앞으로 나아가야 할 길은 서구에 종속되거나 그것에 반대하는 것을 넘어, 스스로의 기반을 세우는 일입니다. 우리는 보다 자유롭게 상상하고, 보다 자율적으로 건설해야 합니다.

에이미 린아시아라는 관념은 경쟁과 협력 중 어느 쪽에 더 가까울까요?

쑨거두 요소가 모두 작용한다고 볼 수 있습니다. 경제를 놓고 보면 결국은 경쟁이고, 그 경쟁을 뒷받침하는 협력은 언제나 임시적인 것에 불과합니다. 정치도 비슷해요. 하지만 문화의 영역, 특히 정신적 창조의 과정은 단순히 경쟁이나 협력이라는 개념만으로 설명하기 어렵습니다. 아시아에서 정신적 산물이 만들어지는 과정은 훨씬 더 복합적이며, 저는 그것을 ‘매개적’이라고 표현하고 싶습니다.

에이미 린‘매개적’이라는 표현이 의미하는 바를 조금 더 설명해 주시겠어요?

쑨거제가 말하는 ‘매개적’이란, 상대를 단순히 비교나 경쟁의 대상으로 보는 것이 아니라, 서로의 작업과 정신적 산물을 통해 자신의 상상력과 창작 동력을 확장하는 관계를 뜻합니다. 다시 말해, 타인의 작업을 통해 나의 작업이 자극받고 성장하며, 동시에 독자성을 유지하는 것입니다. 예를 들어 지금까지 중국과 일본의 관계는 주로 물질적 교류의 차원에서만 논의되어 왔는데, 그것은 제한적인 이해 방식입니다. 진정한 관계는 더 심화된 차원에서, 즉 정신적이고 상호적인 교류로 이루어져야 합니다. 그래서 저는 중국과 일본의 관계를 경쟁이나 협력이 아닌, 매개적이고 상호적인(reciprocal) 관계로 이해해야 한다고 생각합니다.

에이미 린올해(2015년)는 제2차 세계대전 종전 70주년입니다. 한국과 일본, 중국과 일본 사이에는 여전히 긴장이 남아 있습니다. 예술이나 문화가 이런 긴장을 완화시킬 수 있다고 보시나요?

쑨거여러 관점에서 생각해볼 수 있겠지만, 이상적으로 문화는 국경을 넘어 국가 간의 대립과 긴장을 완화할 수 있습니다. 그러나 현실은 그렇게 단순하지 않습니다. 예술가들은 대부분 자신의 언어나 문화적 뿌리를 통해 정체성을 형성하지만, 실제로는 그 정체성을 충분히 성찰하지 않은 채 활동하는 경우가 많습니다. 문화가 국가 간의 긴장과 제약을 넘어 설 수 있으려면, 예술가는 먼저 자신의 정체성을 깊이 성찰하고, 그 다음으로 국가나 민족을 넘어서는 더 큰 정체성을 구축해야 합니다. 이런 과정이 결여되면 넓은 차원의 정신적 산물을 창조하기 어렵습니다. 국가 단위를 초월한다고 해서 국가 정체성이 사라지는 것은 아닐테지요. 제가 강조하고 싶은 것은, 언어나 문화적 배경이 창작의 근본적인 원천임은 분명하지만, 국가 정체성을 절대적인 전제로 삼을 필요는 없다는 점입니다. 문화적 정체성에는 여러 층위의 깊이가 존재하며, 그것이 인간 정신의 깊은 차원에 닿을 때, 비로소 국적의 틀을 매개로 하면서도 그 너머의 인간적 보편성을 반영할 수 있다고 생각합니다.

에이미 린 해외에서 활동하는 몇몇 예술가와 큐레이터들이 떠오릅니다. 그들은 세계를 자유롭게 이동하지만, 어떤 깊이는 느껴지지 않습니다. 국가 정체성이나 자기 문화에 대한 이해가 부족하다면, 어디로든 이동할 수는 있겠지만 결국 새로운 곳에 도달하지는 못하는 것 같습니다.

쑨거좋은 지적이에요. 정체성의 기반이 부재한 예술가에게 미래는, 쉽게 다가오지 않습니다.

IV. 아시아 담론의 생산 플랫폼으로서 현대미술

에이미 린최근 홍콩, 광주, 상하이, 싱가포르, 그리고 중동의 석유 수출국들에서 새로운 문화·예술 기관들이 잇달아 설립되고 있습니다. 이들 기관은 모두 지역적 차원에서 자신들의 입지를 확립하려는 의지를 드러내고 있는데요. 이러한 움직임이 하나의 지역적 시각을 형성하는 것처럼 보입니다. 이런 경향은 아시아적 정체성 혹은 아시아인으로서의 자기 인식에 어떤 영향을 미칠까요?

쑨거 매우 고무적인 현상이라고 생각합니다. 1955년 반둥 회의가 열렸을 당시, 아시아에 대해 이야기하던 사람은 오직 정치인뿐이었습니다. 오늘날 가장 큰 변화는, 여전히 정치인들이 아시아를 논의하고 있지만 이제는 아시아가 그들에게 더 이상 전제로 작용하지 않는다는 점입니다. 반면 예술과 문화의 영역에서는 당신이 언급한 움직임들이 아시아에 대한 새로운 상상과 아시아적 주체성의 형성을 보여주는 상징적인 변화로 볼 수 있습니다. 이는 사회의 여러 층위에서 문화가 주도하는 변화이기도 합니다. 제가 이 표현을 다소 망설이며 쓰긴 하지만요. 여전히 일부 학자들은 아시아를 서구를 위한 연구 대상으로 다루거나, 그저 ‘다채로운 뷔페’처럼 접근하는 데 만족하고 있습니다. 중국의 경우, 일부 지식인들에게는 과거의 일본처럼 아시아를 대표하는 국가라는 인식이 남아 있기도 하지요. 그래서 미술계에서 아시아에 대해 이야기해 달라는 요청을 받을 때마다, 저는 현대미술이 이미 아시아적 원리를 생산하는 중요한 플랫폼이 되었다는 점을 실감합니다. 이는 또한 반둥 회의 시기처럼 국가 단위의 독립운동이 중심이던 정치적 시대에서, 원리와 사유를 탐구하는 문화 중심 시대로의 이행을 상징한다고 생각합니다.

아시아 각 지역에서 열리는 수많은 비엔날레들은 겉으로는 ‘아시아’를 표방하지만, 실상은 지역별 작품을 한자리에 모아놓은 대규모 ‘전시 뷔페’에 그치는 경우가 많습니다. 많은 이들이 ‘아시아’를 이야기하지만, 실제로는 자신이 속한 국가나 지역의 관점에서만 사고하는 경우가 대부분입니다. 때로는 담론의 초점이 지역을 넘어 아시아 전체로 확장되기도 하지만, 그 차이는 결국 자신이 속한 문화를 얼마나 깊이 있게 탐구하는가, 그리고 그 과정에서 원리를 놓치지 않으면서도 얼마나 유연하게 자신을 넘어설 수 있는가에 달려 있습니다. 저는 이러한 ‘자기 초월’의 능력이야말로 아시아적 특성, 즉 ‘아시아다움’의 핵심이라고 생각합니다. 지역 문화를 논할 때 우리는 아시아적 원리를 도구로 삼을 수 있습니다. 그렇게 함으로써 단순히 특정 지역의 문제로 머무는 것이 아니라, 그 문화가 지닌 의미와 가능성을 더 깊이 이해할 수 있게 됩니다. 물론 오늘날 ‘아시아’를 내세운 수많은 전시나 행사가 있지만, 그 안에서 아시아다움에 대한 성찰은 여전히 피상적인 수준에 머무르고 있습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고, 지금 이 시점에 아시아가 관심을 받고 있다는 사실 자체는 분명 의미 있는 일이라고 생각합니다.

에이미 린제3세계에 대해 이야기하셨던 것처럼, 각 국가는 제3세계를 이해하는 방식이 다르다고 하셨죠. 아시아에 대해서도 비슷한 현상이 있는 것 같습니다. 많은 국가들이 자신을 중심에 두고 ‘아시아’ 혹은 ‘세계’를 상상하며, 그 중심 안에서 자신만의 질서를 만들고자 합니다. 이런 상황에서는 아시아 내부의 국가들이 서로를 이해하고 관계를 맺는 과정에서 많은 사각지대가 생깁니다. 우리는 각기 다른 현실과 문화 속에서 살아가고 있기 때문에, 이러한 사각지대를 극복할 방법이 필요하다고 생각합니다. 만약 그것이 가능하다면, 우리는 아시아의 다양한 지역적 맥락을 훨씬 더 분명하게 보고 이해할 수 있을 것입니다.

쑨거 이 문제를 좀 더 풀어서 말하자면, ‘타자’를 이해하고자 하는 욕망이 있어야 합니다. 예를 들어, 저는 중국인이지만 중동을 이해하고 싶은 마음이 있습니다. 여기서 말하는 사각지대는 단순히 지식의 결핍이 아니라, 관심과 동기의 결여를 뜻합니다. 그렇다면 이런 동기는 어디서 비롯될까요? 오늘날 제3세계의 주류 지식인들을 보면, 대부분은 유럽과 미국의 지식 체계에 익숙하고 또 그 자료가 충분합니다. 영어를 못하더라도 번역된 유럽 고전을 읽고, 토론 자리에서는 그것을 권위 있게 인용하죠. 그러나 아프리카에 대해서는 거의 관심이 없고, 배워야겠다는 동기도 없습니다. 그들은 아프리카를 사유나 원리를 생산하지 못하는 지역으로 간주합니다. 이러한 무관심이야말로 서구 중심의 지식 구조와 현실 권력 체계가 만들어낸 사각지대입니다. 더 나아가, 새로운 국가가 등장할 때마다 이러한 패러다임은 반복됩니다. 따라서 이 문제를 단순히 서구의 탓으로만 돌릴 수는 없습니다. 아시아의 모든 사회 또한 스스로를 중심에 두고, 지배적 문화의 요구에 적극적으로 반응하는 경향이 있습니다. 이러한 구조적 문제는 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 서서히 변화할 수밖에 없습니다. 특정한 사상을 내세우거나 예술가에게만 해결을 기대하는 것은 한계가 있습니다. 예술가는 문제를 제기할 수 있지만, 그것을 해결로 이끄는 것은 쉽지 않습니다. 예술의 역할은 문제를 드러내고, 사람들에게 질문을 던지는 데 있다고 할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 중국 사회의 특정한 문제를 환기하고 성찰을 유도하는 것이지요. 그러나 해결은 그 다음의 문제입니다. 한편 아시아의 다른 지역에서 자원을 끌어올 수 있다면 큰 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 중요한 것은 그것이 단순한 차용이 아니라, 스스로를 비추는 성찰의 매개로 작동해야 한다는 점입니다. 그렇게 될 때 비로소 새로운 사유의 지평으로 확장될 수 있습니다.

에이미 린최근 중국, 일본, 한국 간의 예술 교류를 인상 깊게 보고 있습니다. 물론 정부의 외교 프로그램이 지원하는 교류는 제외하고요. 흥미로운 점은, 관찰자로서 보기에 중국이 오히려 다른 아시아 국가들에 가장 무관심한 나라처럼 보인다는 것입니다. 이에 대해서는 어떻게 생각하시나요?

쑨거그 점은 1949년 중국의 건국 이후 지금까지 이어져 온 역사적 긴장과 관련이 있습니다. 1958년의 국가 슬로건은 ‘조영간미(超英赶美, 영국을 뛰어넘고 미국을 따라잡자)’였지요. 이는 우리의 적이 서구에서 비롯되었고, 동시에 우리의 근대적 상상력 또한 서구로부터 왔다는 인식에서 비롯된 것입니다. 이후 문화대혁명과 개혁개방을 거치면서, 지식인들의 사고방식은 정치 중심에서 문화 중심으로 이동했습니다. 당시 많은 지식인들이 유럽과 미국에서 공부했기 때문에, 그들의 담론은 자연스럽게 영어를 중심으로 형성되었고, 주요 관심사 또한 유럽과 미국을 비판하거나 대항하는 데에 집중되었습니다. 결과적으로 문화 영역에서의 상상력 역시 서구 중심적으로 작동할 수밖에 없었습니다. 따라서 오늘날 아시아적 상상력을 발전시키려는 시도는 아직 초기 단계에 있습니다. 이 현상은 순수미술계뿐 아니라 지식 생산 전반에 걸쳐 나타나고 있습니다. 다른 아시아 국가들 즉, 우리 주변의 이웃들에 대한 무관심은 일정 부분 역사적 배경과 구조적 논리로 설명할 수 있지만, 그렇다고 정당화될 수는 없습니다. 다행히 최근에는 이러한 흐름이 조금씩 바뀌고 있습니다. 지난 몇 년 동안 많은 큐레이터들이 저를 초청해 ‘아시아’에 관해 이야기하도록 했고, 그 과정에서 저는 중요한 변화를 체감했습니다. 즉, 이제 예술가들이 이 담론의 전면에 서 있으며, 미술계가 그 변화를 이끄는 최전선이 되고 있다는 사실입니다.

이 글은 2015년 8월 5일 진행된 인터뷰를 바탕으로 하며, 중국어 원문은 쑨거와 에이미 린이 편집하고 다니엘 니에가 영어로 번역한 것입니다. 영문본은 2015년 가을호 『아트리뷰 아시아』에 처음 게재되었고, 2023년에 재편집되었습니다. 본 텍스트는 비영리 목적에 한하여 사용할 수 있습니다.

동아시아 문제에 지속적으로 관심을 가져온 쑨거는 학문의 경계를 넘나들며 중국과 일본의 문학 및 사상에 대한 비교 연구를 지속해 왔다. 현재 중국사회과학원 문학연구소 교수로 재직 중이며, 현대 중국문학, 일본 근대 사상사, 비교문화연구 등을 주요 연구 분야로 삼고 있다. 저서로는 『나하에서 상하이까지: 위기 상태 속 삶』(2020), 『아시아를 찾아서: 세계를 아는 또 다른 방식』(2019), 『역사와 인간: 보편주의에 대한 성찰』(2018), 『사상사 속 일본과 중국』(2017), 『왜 동아시아를 말해야 하는가: 상황 속의 정치와 역사』(2011), 『문학적 위치: 마루야마 마사오의 딜레마』(2009), 『타케우치 요시미의 역설』(2005), 『만연하는 주체성의 공간: 담론적 아시아의 딜레마』(2002), 『아시아란 무엇을 의미하는가?』(2001) 등이 있다.

에이미 린은 상하이를 기반으로 활동하는 큐레이터이자 작가, 비평가다. 상하이 푸단대학교에서 비교문학 석사 학위를 받았으며, 《LEAP》의 창간 편집장(2010–2012), 《ArtReview Asia》의 공동 창간자이자 편집장(2013–2019), 그리고 베이징 롱마치 스페이스(Long March Space)의 디렉터(2019–2021)를 역임했다. 현재는 스쿨 오브 비주얼 아츠(School of Visual Arts)의 그레이터 차이나(Greater China) 대표로 재직하며, 중국과 뉴욕을 오가며 활동한다.

I. What does Asia mean?

AIMEE LINWhat does Asia mean? Does it possess meaning beyond its geographical connotations?

SUN GEOf course. Asia is more than a spatial concept, which is to say, it is more than a geographical concept, and it is also more than a political-historical-geographical concept. In academia, there is now a field called political historical geography in which various political, cultural and historical questions are discussed in the context of where they happened. Asia is indeed a compound concept of politics, history and geography, but in addition to that, I believe it has an important alternative function, one that is often overlooked: its spiritual fūdo character.

AIMEE LINWhat is fūdo?

SUN GE Fūdo refers to the natural geographical characteristics possessed by a given region or geographical space. The combination of these characteristics with the particular spiritual life of people via social activities is called fūdo. [Fūdo, or Fengtu, is a term used by Japanese philosopher Tetsuro Watsuji (1889–1960) in Fūdo: ningen-gakuteki kōsatsu (1935), translated in English as Climate and Culture (1961). The term signifies ‘wind and earth… the natural environment of a given land’.] So the concept of Asia is at the very least a particular natural geographical space that bears the weight of political, historical and spiritual culture produced by human activity within it. The various spiritual products of society and the humanities are discussed within the context of a particular space.

AIMEE LIN‘Asia’ was originally a name that outsiders used for a specific geographical space. Does Asia, or the concept of Asia, mean something to the people who live within this space?

SUN GE Prior to modern times, ‘Asia’ did not have any connotations of subjective identification, but in the twentieth century that changed. From the Crusades, when the term referred only to Asia Minor (Anatolia), until the turn of the twentieth century, as Europe gradually subjected the world to colonialism, the Asia discourse of the West was consistently one in which Asia served as Europe’s ‘other’. During the powerful classical period of the Islamic world, this ‘other’ was a formidable foe. In modern times, this ‘other’ has become a source of comparison – evidence against the predominance of European culture. Until the end of the Second World War, European ideology did not acknowledge that Asia could be an equal counterpart with which mutual understanding was possible. Even then, such a relationship was merely a possibility. And to this day, this possibility remains relatively marginal in Europe.

As for Asia, it was not until the end of the Second World War that a relatively widespread trend emerged in which the meaning of ‘Asia’ was reversed in order to connote a subjectively identified political symbol. At that point, one could no longer say that Asia was merely a concept created by the West. This change in the symbol was marked by the Bandung Conference of 1955 [the meeting of African and Asian states that anticipated the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement of countries]. Of course, that was just one phase of its evolution. In terms of major historical trends, the general development of the Asia discourse began in the twentieth century as ‘Asia’ was transformed into a symbol of self-identification in some societies in the Asia region. Japan was the first place where this self-identification occurred. The growth of Asianism in Japan reached its peak with Japan’s victory in the 1904–5 Japanese–Russian War. The Japanese saw this war as a war between races: a victory of the yellow race over the white race. In his speech on the ‘Three Principles of the People’ [1905], [Chinese revolutionary] Sun Yat-sen recounted how, on his boat trip on the Suez Canal, an Arab asked him if he was Japanese. At that time, Arabs rarely expressed their sense of solidarity with East Asia, but the Japanese–Russian War had contributed to Arabian identification with Asia as part of the yellow race. The unfortunate thing is that Japanese Asianism accompanied war, and their methods of war were imitations of European colonial methods. So Japan’s path was not one of genuine Asianism; it was a path of Europeanism. This Europeanism was most typically exemplified by the Second World War and Japan’s invasion of East and Southeast Asia. Japan’s colonialism, along with its methods of advancing the war, was completely in the mould of early European colonialism.

Therefore, if it can be said that Asianism exists in Asia, then this Asianism has many faces, and tension exists between them. But we can say without value judgement that in the late nineteenth century a trend emerged in which several different parts of Asia, in many different forms, began to cast off the cultural symbols of the Western ‘other’ and adopt subjective symbols of self-identification. It was a historical trend, and so the earlier period of history in which ‘Asia’ was named by the West cannot be used to explain the use of the nomenclature of Asia by Asian people after the turn of the twentieth century.

AIMEE LINThen what changes have occurred in the meaning of this idea of Asia since the end of the Second World War?

SUN GE After the Second World War, this idea of Asia was used at the Bandung Conference in the context of Afro-Asia – ie, Africa and Asia – and the national independence movements of the two continents. At that point, a core aspect of Asian identity was the national independence movements at the state level. During the process of Asia’s rise during the 1950s, the principle significance of Asia as a political unit was political subjectivity. Other than Japan, the vast majority of Asian regions had experienced either direct or indirect colonisation. In this context of being discriminated against and feeling humiliated, Asia experienced a sharp surge in solidarity in the 1950s. Asia is not like Europe in that it cannot be roughly integrated on the basis of a single religion. There are at least three major civilisations in Asia, and more than three main religions that cannot be easily integrated. However, the Bandung Conference symbolised a period of integration during the 1950s in which the concept of Asia was spread vigorously through virtually the entire region. As these states gained independence and sovereignty, so the situation changed.

AIMEE LIN Roughly when did that happen?

SUN GE I would say it happened as the Cold War structure began to disintegrate. Asia began to split up during the 1970s, because at the time the entire continent was facing a developmental problem: how to achieve modernisation. The result was all sorts of dialogue, exchange and cooperation between Asia and the West. Thus, after the 1970s, a new round of colonialism began, but this time in an invisible form. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in the early 1990s, Asia was faced with the question of forming new alliances. So new coalitions, like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation or the BRICS countries, are in fact symbols of Asia’s reorganisation of international relations. In these circumstances we discover that Asia is already incapable of acting, in terms of geography, as an independent unit in order to emphasise its identity. For example, the Six Party Talks in Northeast Asia are a major thing for Asia, but nobody raises an eyebrow at the participation of two non-Asian states (Russia and the United States). By means of the Second World War, the United States had already completed its internalisation in Asia, and especially in East Asia. These circumstances have led some people to say that Asia has not been established as a reality. From a geographical perspective, Asia does indeed seem unable to cast off the countless claims of other regions. The solidarity of the 1950s symbolised by the Bandung Conference has indeed disintegrated.

II. Asia as Principle

AIMEE LIN So the integration of Asia as a geographical space was not achieved.

SUN GE That’s right. But if we recall our initial discussion, we said that Asia is more than a geographical concept. It is also an amalgamation of political, historical and spiritual culture. It symbolises people’s spiritual activities, and the fūdocharacter of social and artistic activities. In this sense, I believe that today we have reached a stage in with we can reorganise and rephrase the discussion by treating Asia as a set of principles.

AIMEE LIN You have previously written about the question ‘how does Asia mean?’ But it sounds quite new when you mention ‘Asia as principle’.

SUN GEI reached this step quite recently. In my opinion, the present Asia discourse is still off the mark. If Asia does not have its own principles, then it truly is no more than field material within the framework of Western discourse. To date, that is how Asia has been treated in Western and Chinese scholarship, but I believe that we should now produce Asian principles. However, producing Asian principles is not only for the benefit of Asian people. I think it is a historical responsibility for the benefit of humankind. Asian principles are simply principles that are relative to European, African and Latin American principles. The discussion of them is not an intellectual activity intended to resist or replace the West.

AIMEE LIN Before we start discussing Asia as principle, I want to ask you: do art or culture play a role of shaping the identity of Asia or the idea of Asia?

SUN GE Art and culture give form to spiritual energy. The spiritual activities of humans must have form before they can present themselves to us. Art utilises the form of direct observation to communicate this spiritual information. I can say that, to date, the art I have been exposed to, such as the fine arts, theatre and film from East Asia, are Westernised in the mainstream. Their Asian-ness is insufficient.

AIMEE LIN Are you saying that the reasoning behind it lacks that awareness of so-called Asian subjectivity, and it unconsciously uses Western methods or Western perspectives?

SUN GE Yes, it uses Western perspectives. The most typical example is Zhang Yimou: all of the expressions of Chinese-ness in his films are intended to cater to the requirements of Hollywood. Of course, there are other ambitious artists who are not as superficial as Zhang Yimou. They are more inclined to seek an Asian element, but these artists, including art curators, have an essentially Western field of vision. For example, one deeply rooted idea in the minds of contemporary artists and curators is modernity. If you do not let them talk about modernity, they basically cannot function. This is a trend that exists today, and I do not believe that it should be negated, because in a certain sense it expresses the consequences of Western infiltration of all of Asia, from politics and economics to culture. But in fact, there are fringe cultural and artistic activities in which comparatively Asian elements are developing. This development requires nourishment, but I believe that Asian intellectuals seem to have not yet reached this point. It requires a process.

AIMEE LIN Can you give an example of the cultural activities you mentioned?

SUN GEOne example is the Japanese playwright Sakurai Daizo. His Tent Theatre is extremely Japanese. The performances draw on the lives of ordinary, lower-class Japanese people. It is a very special artform. Sakurai is very imaginative, but the number of intellectuals who can appreciate his Tent Theatre is limited. Yet Sakurai has received acclaim throughout East Asia. Young intellectuals are especially fond of his plays because his methods are very fresh. But the Asian element that he contains must evolve. Another example is the printmaking activities in the Korean city of Gwangju. There are also some artistic activities in Okinawa, such as photography. That area retains its original religion, which resembles shamanism. There is a photographer who photographs a sacrificial ritual that takes place every February in the Miyako Islands [the largest archipelago in Okinawa Prefecture]. But this kind of genuinely indigenous artistic or literary activity that does not utilise Western concepts and hermeneutics is to date very difficult to circulate and share widely. This is a basic fact, but this wellspring possesses powerful vitality. It will not disappear.

AIMEE LIN Perhaps the explanation lies in the mechanisms of acknowledgment and circulation in contemporary art. After all, the people within these mechanisms have no ability to see and understand this kind of art.

SUN GE I think this is a matter that requires a bit more time, and moreover, it is not just a matter for Asian people to resolve. The status and function of the Western intelligentsia, or one could even say the entire Western world, changes. The Western intelligentsia’s conception of Asia is also changing. I think that ambitious intellectuals, whether they are Asian or Western, will not be satisfied solely with questions of so-called modernity and postmodernity when the reality of our lives is so diverse and abundant. The day will come when everybody’s experience will be fresher and more abundant. In this sense, art and culture can play an extremely important role, but to this point, they have really not done much.

AIMEE LINThere are some Westerners who believe that the language barrier is the reason that Western people define Asian identity through culture. They can only mechanically imagine other cultures. What do you think of this opinion?

SUN GE I think it is definitely one factor, but it does not tell the whole story. The lack of understanding of Asia in the West is in a certain sense due to the excessive autonomy of the West, which has only just begun to change. When Westerners begin asking this kind of question, it demonstrates that they have begun to recognise the problem. Yet to this day, the majority of Western European and North American intellectuals lack genuine curiosity about Asia, and the reason for this is certainly not the language barrier.

AIMEE LIN Is it a kind of insularity in their own cultures?

SUN GE That goes together with the historical trends in politics and economics of recent times: the West going forth to conquer the whole world from an advantageous position. Culture cannot be separated from politics and economics, even though they each have their own characteristics. Cultural people in the West with a genuine awareness of Asia are definitely on the fringes.

AIMEE LINThere are very few.

SUN GE But I believe there are some. When I discuss the China question with Western European and North American intellectuals, they first trot out a few frameworks, such as modernity, postmodernity, rationality, individual rights, scientism and evolution. All of these frameworks in fact constitute the quite mature cultural structure of modern Europe, and Western intellectuals have been instructed within this cultural system to see them as normal. But the question is, what do they do when they are faced with the East, which does not share these traditions but only imports parts of those elements (from those frameworks)? It seems that every Western intellectual I encounter always tries hard to take whatever unfamiliar experience he or she witnesses and hesitantly cram it into these frameworks, and use them to interpret it.

AIMEE LIN When you put it that way, the necessity of Asia as principle becomes apparent, because to them as well this is a huge challenge, a very difficult task.

SUN GE Yes. ‘Asia as principle’ is not an empty phrase. It means that we must redefine what is universal. We must start from this perspective: any intellectual or spiritual activity is endemic, ie, governed by fūdo. This means that you cannot take your European or North American partial experience to other regions and treat it as a global experience shared by all humankind. This kind of approach should be negated right from the start. This is the demand that Asia as principle makes of humanity. At present, if you view Asia from the perspective of European principles, then you will use an allegedly universal imagination to view Asia. So you will search for modernity in Asia, and search for scientific rationality. It is not just Westerners who do this. Asian people also do this.

AIMEE LINThat is because in our minds we have already become like them due to our education and academic training. But our lives, and our physical and sensory experiences, go beyond that mental aspect.

SUN GE Everybody with this kind of educational background has trouble interpreting the change that is occurring in the various Asian societies. For example, how should we interpret the present high degree of mobility, or more specifically, the massive phenomenon of migrant labour in Chinese society? The point is not to give a basis of legitimacy to the existence of every society. This is a kind of intellectual work, so it is not about affirming or negating. What we want to do is to understand. I do not make art, but from the perspective of intellectual history, this issue is extremely pressing. This is what compels us to discuss Asian principles. I think Asian principles in their most simplified form are a universalism based on the premise of the coexistence of a diverse plurality of physical phenomena.

AIMEE LINWhen you say physical phenomena, is that the fūdo you mentioned?

SUN GE That’s right.

III. The Prerequisite for Asian Art

AIMEE LINFrom your perspective as a scholar, is there such a thing that can be called Asian art, and if so, what constitutes the so-called Asian-ness of this art?

SUN GEThis is truly a big question. First of all, I think the existence of Asian art is not only possible but necessary. However, the existence of Asian art is definitely a diverse existence. So when we talk about Asian art, the prerequisite is that it does not have representatives. We cannot say that Western art has definite representatives – in fact it is very easy to name several different schools of Western contemporary art. I believe that Asian art is the same. But there is also a way in which it differs from Western art, in that there is no ‘primariness’ that encompasses Asian art.

AIMEE LINIt has no unifying characteristic.

SUN GEThat’s right. Over at least the last one or two centuries of forceful moulding by the West, we have become accustomed when discussing a given field to identify a representative and talk about their primariness. What we should do now is discuss the plurality of a field, but people have not yet formed this habit. This is the prerequisite for discussing Asian art. The reason we need this prerequisite is because Asian art cannot be unified. It is varied and plural. The Chinese philosopher Chen Jiaying has proposed the terminology of ‘the particular’, which emphasises the combination of the individual and the characteristic. I think Asian art comprises countless particulars, but what we want to talk about is not a buffet. If it is a buffet, then Asian art does not exist, because it is too dispersed. There are relations between the particulars, and we must use Asian principles to interpret these relations. What is the meaning of these relations? Well, the various particulars are absolutely not the same, and the ways in which they coincide with each other are also not uniform. In establishing these relations between particulars, there is no good and bad. This idea does not comport with European principles. Asian art takes form when we have the goal of establishing relations between the particulars through mutual understanding, through self-liberation and through the individual’s transcendence. This is related to the need for us to change our practice of appreciating Asian art on the basis of European modernity and postmodernity. Our current custom of appreciation is to first translate our culture into English, and then use it to enter other cultures.

AIMEE LINAre there some aspects of this idea of Asia that contradict or oppose the Western world and its theories?

SUN GEYes, but I think that point is not so important. Opposing the methods of the West has been necessary thus far, but as soon as you oppose something, you become subject to the limitations of your opposition.

AIMEE LINYou are ‘countered’.

SUN GEYes, which means that this part of the production of knowledge is transitionary, and not particularly constructive. For example, postmodernity is restricted by modernity, so it cannot be free. Asia is restricted by the West: an unavoidable historical fact. If you want to work towards genuine self-liberation from this state of being restricted by the West, I think criticism is ineffective. You must relativise the West, not negate it. The crucial thing is to build our own framework of understanding and organisation that includes the effects of the Western infiltration of Asia. Negating and opposing the West has no constructive function. The establishment of Asian thought and culture requires structural construction. At present, two relatively familiar methods of Eastern intellectuals are those of critiquing the West and reforming the West. These two modes are both significant, and they are both closely linked to the West itself. But I believe that they are transitionary. They form the foundation on which we must engage in our own construction, unrestricted by the West and not predicated on opposition to the West. We must imagine more freely and build more autonomously.

AIMEE LIN Is this idea of Asia driven by competition and opposition, or by cooperation?

SUN GEA little bit of each. If we’re talking about the economy, then it is definitely competition, and cooperation, which serves the needs of competition, is always provisional. Politics is similar. But I think competition and cooperation are a difficult terminology to use to understand the realm of culture, and particularly the creation of spiritual products. In fact, I think the creation of spiritual products in Asia is intermediary.

AIMEE LINWhat do you mean by intermediary?

SUN GE I mean that I treat my counterpart as a medium, and draw on their work and their spiritual production to fuel my own imagination and creative motivation. Intermediary means that my work is not entirely their work, and their work cannot interpret my work, but if we did not understand each other, then my work would not be the way it is. For example, the spiritual production between China and Japan has to date been imagined in an extremely material form, which is a low-level way of thinking. The truth is that we should take the next step, into a field of greater quality. The relationship between China and Japan should be intermediary, or reciprocal, which is neither competition nor cooperation.

AIMEE LINThis year is the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. Historical factors have created an extremely powerful state of psychological tension between, for example, South Korea and Japan, and China and Japan as well, which has still not dissipated. Can art or culture, through certain means, dissipate this tension?

SUN GEThere are several ways to look at this. Ideally, culture will transcend borders, and in this way it can dispel the imagined opposition between different societies created by national tension – for in fact this opposition exists only in the imagination. But the truth is not that simple. When cultural workers do their thinking and creating, it is their mother tongue that determines their identity. The vast majority of cultural people rarely reflect on this self-identification. If culture is to transcend the tense mentality between nations, then cultural people must first reflect on the very presupposition of their self-identification, and then form an identity for themselves that is greater than their national unit. I believe that people who cannot transcend this specific unit cannot create truly world-class spiritual products. This is not to say that if you transcend your national unit then you have no nationality. No, what I want to emphasise is that of one’s fixed cultural characteristics, one’s mother tongue, is certainly a fundamental source of one’s creative practice, but one need not treat one’s nationality as an absolute presupposition. I believe that there are various levels of depths in cultural identity. If a cultural identity reaches the depth of human spirit, it will reflect it [human spirit] by means of nationality, while resisting an abstract, general expression.

AIMEE LIN I am reminded of certain artists and curators who live abroad. They can freely travel to the most distant parts of the world, but their spirituality seems somewhat lacking. Once a person completely ceases to believe in nationality or their original culture, they may be able to depart a place, but they ultimately never arrive at a new place.

SUN GEYes, I think that is very accurate. Artists with no roots have no prospects.

IV. Contemporary Art as the Production Platform of Asia Discourses

AIMEE LINRecently, new cultural and art organisations or institutions have been established in Hong Kong, Gwangju, Shanghai, Singapore and the oil-exporting states in the Middle East. They all proclaim the intention of establishing their position on a regional scale. Together, they appear to present the formation of a regional field of vision. What effect does this trend have on our Asian-ness or our self-identification as Asian people?

SUN GE This is a very encouraging phenomenon, because when the Bandung Conference was convened in 1955, the only people talking about Asia were politicians. Today, the biggest change is that our politicians are still talking about Asia, but Asia is no longer a presupposition for them. But to people in the worlds of art and culture, this trend you mention is a symbolic change that represents the imagination of Asia and the formation of its subjectivity, guided by the cultural world at different levels of society – although I use that word reluctantly. Some people who do academic research are still content to treat Asia as either a field for the West or a big buffet. As for China, it is treated by some intellectuals as a representative of Asia, just like Japan was previously. So when the artworld invites me to talk about Asia, I recognise that contemporary art has already become an important platform for the production of Asian principles. It also symbolises the transition from the politics-driven period of the Bandung Conference, where the subject was Asian independence movements at the state level, to a culture-driven period in which we search for principles.

The various biennials in the region may take place in Asia, but the content of the exhibitions are basically a big buffet of their own region. In a lot of places, when they say Asia, they are really talking about themselves. Sometimes they switch to talking about Asia, so what is the difference between the two? It lies in whether or not you are able to deeply explore the principles of your own culture, and if you are, whether or not you are able to use open, principled, relativised methods to transcend yourself. The ability to transcend the self is one of the most important characteristics of Asian-ness. When you discuss a local culture, you can take the approach of Asian principles. This culture of yours can possess Asian-ness, and you can use the approach of Asian principles to address your local issues, which are otherwise merely a particular situation. So I don’t think the question of being a particular region is that important. The crucial thing is how you do it. Conversely, we see many events with ‘Asia’ in their title that assemble large quantities of Asian things to exhibit, but the Asian-ness of these events is in fact quite shallow. But regardless, I think it is an important phenomenon that Asia is now obtaining attention.

AIMEE LINOn the subject of the Third World, you once said that each state’s understanding of the centre of the Third World is different. When we discuss Asia, we face the impulse of different states to establish a world or an Asia in which they are at the centre. In these circumstances, there are many blind spots in how states within Asia relate to and acknowledge each other. Each of us inhabits a specific reality and culture, and we require an operational solution to overcoming these blind spots in our fields of vision. If we can do that, then we can see and understand the regional situations within Asia.

SUN GE To elaborate on that point, I would say that the problem can be identified. In what circumstances should we seek to understand ‘the other’? For example, though I am a Chinese person, I have the desire to understand the Middle East. The blind spot is a problem of motivation, not a problem of knowledge. Where does this motivation come from? We can see that most intellectuals in the Third World today, particularly in the mainstream, have quite complete repositories of European and American knowledge. Even if they do not speak English, they read the European classics in translation, and quote them authoritatively in discussions. But they have no interest in Africa, no motivation. They think it is a place that does not produce ideas or principles. This kind of blind spot is the result of the prevailing Western-centric power structure of knowledge and reality. Moreover, whenever a new nation-state is formed, it reproduces this paradigm. So you cannot locate this problem solely in the West. All of the societies of Asia are like this. They put themselves at the centre and actively respond to the demands of the dominant culture. To an extent, this situation will be resolved by history. This is not something that we can rely on artists to guide us through by emphasising certain ideas – that is useless. We must pay attention to the limitation of the effectiveness. Artists can do some work, for example urging people to resolve certain problems in Chinese society. But the solutions to these problems are not easy to identify. Accessing the resources of other regions of Asia can be very helpful if they can be transformed into the intermediary of reflection, and will naturally lead to new ideas.

AIMEE LINI have recently been observing artistic exchanges between China, Japan and South Korea (not including art programmes sponsored by government cultural or diplomatic initiatives). As an observer, I sense that China is the state that least cares about other Asian states. How do you view this issue?

SUN GEI think there is some truth to your observation, which is related to the anxiety that has afflicted the entire state since it was established in 1949. In 1958, the national slogan was chao ying gan mei: ‘Surpass England and Catch Up with the United States’. This was because our enemies came from the West, which was also the source of our modernised imagination. Once the state had been established and society began to develop, that is to say, during the reform period that followed the Cultural Revolution, the political modes inherited by the intellectual class were transformed into cultural modes. So you see our leading intellectuals are those who studied in Europe and the United States. Their discourse is essentially an English-based discourse. Their only contribution is either to critique or to reform Europe and the United States. Given this framework, our imagination of international relations in the cultural field essentially runs on a Western track. As a consequence of these circumstances, the present effort to develop an Asian imagination is a nascent one. This fact influences the fine-arts world as well as other fields that overlap with the intellectual world. There is a certain historical logic to our neglect of other Asian states, of our neighbours, but that is not a justification. Now, things are beginning to change. In recent years, curators are always dragging me out to talk about Asia, which has led me to recognise what I just mentioned: cultural people have moved to the front. The artworld has moved to the front.

Interviewed on 5 August 2015, the Chinese text was proved and edited by Sun Ge and Aimee Lin and translated into English by Daniel Nieh. The English text was first published in the Autumn 2015 issue of ArtReview Asia and re-edited in 2023. Use of the text is for non-profit purposes only.

Interested in the issue of East Asia from early on, Sun Ge has conducted comparative research on the literatures and philosophies of China and Japan across the boundaries of academic disciplines and departments. Her fields of interest include modern Chinese literature, the history of modern Japanese thought and comparative cultural studies. Her major works include How Does Asia Mean?(2001), Space of Pervasive Subjectivities: The Dilemma of Discursive Asia(2002), The Paradox of Takeuchi Yoshimi(2005), The Literary Position: Masao Maruyama’s Dilemma(2009), Why Shall We Talk About East Asia: Politics and History in Situation(2011), Japan and China in History of Thought(2017), History and Humanity: Reflection on Universalism(2018), In Search of Asia: Another Way of Knowing the World(2019), From Naha to Shanghai: Living in Critical State(2020)

Aimee Lin is a curator, writer and critic based in Shanghai. Master of Comparative Literature from Fudan University, Shanghai. Formerly founding editor of LEAP(2010-2012), co-founder and the Editor of ArtReview Asia (2013-2019), and Director of Long March Space, Beijing (2019-2021). Lin currently works as the Greater China Representative of the School of Visual Arts, for which she travels between China and New York.

“어떠한 제한도, 또 안 된다는 금지도 없어요”, 하지만….

“어떠한 제한도, 또 안 된다는 금지도 없어요”1, 하지만….

여러 아시아 미술계의 서로 다른 여러 당신께,

우리는 몇 년간 동남아시아를 ‘남동아시아’로 줄곧 바꾸어 불렀습니다. 그러면서 우리의 대화는 우선적으로, 언어 제국주의와 서구 조형 언어의 이식이 남긴, 흔적을 지닌 미술과 자료가 흡수되는 과정을 살피는 방향으로 이어졌습니다. 줄곧 자국과 타국의 시각문화에 내재한 목적성과 이를 꾸리는 사유가 생산 주체별로 상이했음을 이해하려 했고, 2020년대의 연구자와 비평가의 시각은 어떠해야 할지를 토론했습니다. 더불어 AIC의 토대가 되기도 한 쑨거의 주장을 수용하면서, 우리는 서구 근대 중심적 세계관에 대한 지적 저항과 대안을 마련할 아시아의 지대 중 하나인 남동아시아를 적극 탐색해 보겠다고 제안했습니다. 실제로 태국·인도네시아·베트남·필리핀·싱가포르 등은 복합적인 언어 번역과 사고 체계가 작동하는 사유 공간입니다. 특히 20세기 미술을 들여다보면 남한과 남동아시아 국가들은 일본의 제국주의적 식민 역사, 국가주의와 개발주의에 관한 공통 감각을 보유하고 있음에도, 때론 유비할 수 없을 정도로 유별한 시점에 따른 작품들을 표출해 왔습니다.

미술계 일원들이 내부적으로 주도한 남동아시아 미술은 줄곧 서로에게 우호적인 교류와 공동체적 창작의 모델이 되어왔으며, 동시에 의도적으로 은폐된 기억의 연결과 회복의 양태를 드러내 왔습니다. 물론 그 결괏값 모두를 긍정하기엔 불가능한 지점도 존재하나, 우리는 복잡다단한 검열의 얼굴을 마주하면서도 앞서 언급한 주제 의식을 드러낸 미술 앞에서 보편성과 지역적 사유라는 특수성의 공존을 이해했습니다. ‘여러 아시아 미술’을 알아가는 방법으로 ‘오역하기’를 일삼다 보니, 남한에서 함께 획일적 집체교육을 받은 또래 연구자의 부름에 응답할 기회도 생겼습니다. 초여름, 우리는 승아에게 동시대 아시아, 특히 남동아시아 미술이 ‘미술로서’ 존재하려면 개인이든 집단이든 역사·정치·경제·젠더·계급의 문제와 변동성을 내부로 끌어들일 수밖에 없다는 가정을 바탕으로, 태국의 제도와 작품 그리고 기존에 발행된 텍스트를 독해하겠다고 회신했습니다. 당신께서는 ‘왜 태국이냐’라고 물으실 수 있을 겁니다. 그 이유를 간단히 말하자면, 일본이 주창한 ‘대동아공영권(大東亞共榮圈, Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere)’의 유령이 한때 일본의 식민지였던 국가들의 시각문화에 잔존함을 살폈던 2024년의 경험 때문이었습니다. 저희는 전쟁에 기반한 허구적 프레임을 미적 경험의 한 양태로 정착시킨 일본이, 그들의 식민 체계에서 ‘장자’로 여겼던 태국의 시공에서 배태된 미술의 양상이 궁금했습니다.2 태국의 예술 생산 조건이 여타 남동아시아 국가들과도 상이하다는 점에도 우리는 주목했습니다. 절대 왕정, 도시와 농촌으로 이분화된 구조 안에서 이루어진 근대화를 반영하는 미술을요. 동시에 지금까지의 ‘태국 미술’이 어떠한 관점으로 읽혀왔는지를 되짚었습니다.3 예를 들어 우리는 리크리트 티라바니자(Rirkrit Tiravanija, 1961~)를 ‘관계의 미학’을 대표하는 외국 작가로만 대했던 사실(심지어 작가가 관객과 그린 카레를 나누지만)에 관해 얘기했습니다. 우리는 그의 작품에서 곧바로 물질적인 ‘태국’을 떠올리지 못했던 까닭은 작가의 실천이 남동아시아라는 형이하(形而下)적 맥락으로 읽힌 것이 아니라, 서구 큐레이터의 담론으로 개념화된 미술로서 한국에 수입되었기 때문이라는 결론을 얻을 수 있었습니다. 나아가 작가의 작업이 자전적 특색과 음식이라는 물질을 매개로 선택 했음에도, 우리는 이를 동시대 서양 미술을 구성하는 하나의 예시로 인식해왔음을 자각하고, 반성하게 되었습니다.

이렇게 태국이라는 실체를 탐색하고자 착수한 원거리에서의 ‘읽기와 질문하기’는 물리적 발디딤, 즉 ‘내가 머무는 땅과 나의 사유가 같은 곳에 있으며, 이를 초월할 수 없다’라는 자각과 함께합니다. 1990년대생 연구자로서 우리는 코로나19 팬데믹을 거치며 물리적 한계를 인지했고, 타자의 형상을 온·오프라인 리서치로 이해하거나 메타비평을 시도해 가고자 했습니다. 이러한 외부적 조건은 우리가 모르는 대상을 ‘이미 알고 있다’라고 넘겨짚지 않는 것, 쉽게 동일시하지 않고 거리를 유지하는 것, 그러므로 다양한 매질과 물음으로 상대를 새로이 알아갈 것이란 규칙으로 이끌었습니다. 같은 맥락에서, 우리는 AIC가 제시한 “행위 주체와 어떻게 더 감성적인 ‘돌봄’의 가능성을 만들어갈 수 있는가?”라는 문장에 다음과 같은 질문을 덧붙였습니다.

역사 해석의 충돌이 지속되는 태국의 현대미술사를 분석할 때 우리가 채택할 수 있는 관점은 무엇인가? 방콕 중심의 다층적 검열, 불교문화의 도상과 상투적인 주제를 반복하는 경향 등 태국 미술이 동시대적 공동체의 상상력을 포용하지 못하게 만드는 요소에 어떻게 반응할 것인가? 복수의 ‘그것’을 무시하거나 차치한 채 작품을 독해할 수 있는가? 남동아시아 예술, 특히 태국 미술의 어떤 요인을 작품이 ‘순수 예술’로 인정받기 위한 필수 조건이라 말할 수 있는가?

질문은 끝없이 이어지겠지만, 동시대 태국 시각문화의 일면에 관한 해답을 주었던 데이비드 테(David Teh)의 여러 글 가운데, 우리는 「순회적 영화: 아피찻퐁 위라세타쿤의 사회적 초현실주의(Itinerant Cinema: The Social Surrealism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul)」로부터 길어 올린 생각을 말씀드리고자 합니다. 이 글은 실파콘 중심적인 미술(Fine Art)을 비판하고 1970년대 이후 수도권 외부의 치앙마이와 북부 지역에서 등장한 대안적 성격의 미술, 그리고 이후 태국의 면모를 독자적으로 재현해 온 무빙이미지, 그중에서도 영화를 다룹니다.4 그 속에서 우리는 1955년 찟 푸미삭(Jit Phumisak, 1930-1966)이 주창한 ‘삶을 위한 예술’ 개념과 순턴푸(Sunthorn Phu, 1786–1855)와 같은 걸출한 작가들이 써온 태국의 전통 시 장르인 ‘니랏(Nirat, นิราศ)’ 형식의 호응을 살필 수 있었습니다. 이에 우리는 배움을 넘어 그 형식과 내용을 차용해 지금, 당신께 편지를 띄웁니다. 태국으로부터 발원한 글과 이미지를 남한에서 독해한 후, 동료들과 함께한 공부의 여정과 감정적 경험을 그러모아 당신께 전해드리기에도 탁월하다고 여겼기 때문입니다. 어떤가요? 이 서간이 상호 배움을 통한 지식 생산, 콜렉티비즘, 자기이론의 씨앗이 될 수 있을까요?

하지만, 그리고, 물론, 이 편지로 우리가 성급하게 태국 미술과 초국가적 미술계에 보편화된 연대 의식을 피상적으로 엮어보려 한 것은 아닙니다. 앞서 말했듯, 우리는 모국어도, 우리의 지대와 의식도, 주어진 연구의 환경을 뛰어넘을 수 있다고 여기지 않기에 섣부른 긍정으로 이 편지를 결론지으려 덤비지도 않을 것입니다. 각 공동체의 지향을 하나로 봉합할 수 있다는 낙관주의와 먼 ‘밀레니얼 세대’로서, 우리는 동시대 태국의 예술과 무빙 이미지가 보편적인 정치적 민주주의를 지향하는 듯하다가도, 어느 순간 모호함 속으로 숨는 듯한 인상을 자주 받았기 때문입니다.5 다만 당신께 말을 걸면서 태국 미술을 바라보는 내외부의 시각과 세대별 관점의 간극을 좁혀가고 싶습니다.

이같은 목표를 위해 우리가 주목한 것은 태국의 몸체에서 자라난 물건들과 이야기가 고착된 사진, 그리고 시간성으로 전위된 무빙이미지였습니다. 이는 그것이 실제의 시간과 비례하는, 개인적이면서도 사회적인 문제를 다룰, 독립성 확보를 일정하게 행해온 장르라고 판단했기 때문입니다. 물론 이는 기예나 도상적 전통보다 작품 제작 의도에 과도하게 편중해 장르를 편식한다는 비판을 받을 수도 있습니다. 그러나 내외부적으로 전략적 ‘절충’이 중시되어 온 ‘태국이라는 사유 공간’의 실체를 언어로 굴릴 수 있는 동력이 됩니다. 외부적 검열과 내부적인 냉소 또는 비판적 관점이 한 작품 안에서 ‘내부 필터’로 작동하는 것도 특징적입니다. 수수께끼 같은 작품의 면모는 분명 질료와 연출로부터 촉발되기에 흥미롭지만, 주제가 우회적으로만 펼쳐지기에 한국 관객으로서는 작품의 태도가 다소 수동적으로 느껴지기도 합니다. 일례로, 사리나 사타폰(Sareena Sattapon, 1992~)의 〈너와 나 그리고 우리가 만난 모든 이들(You and Me and Everyone We Have Met)〉(2024)은 거울상으로만 볼 수 있는 무빙이미지로, 한 지점에서 전체를 관찰하거나 촬영하기 어렵습니다. 식별할 수 없는 표면이 재생되는 모니터를 특수한 유리판으로 비추어야만 우리는 작가가 선별하고 번역한 태국어와 일본어, 영어가 교차하는 도시 풍경을 볼 수 있습니다. 물론 프라팟 지와랑산(Prapat Jiwarangsan, 1979~)의 2024년 연작 〈기생 가족(Parasite Family)〉, 〈시암 가족의 초상(The portrait of Siamese Family)〉와 같이 기성세대의 사진과 왕권을 암시하는 이미지를 가일층 직설하는 경우도 존재하지만, 작은 조각으로 잘린 인물 사진 더미는 메시지를 일부 분쇄합니다.

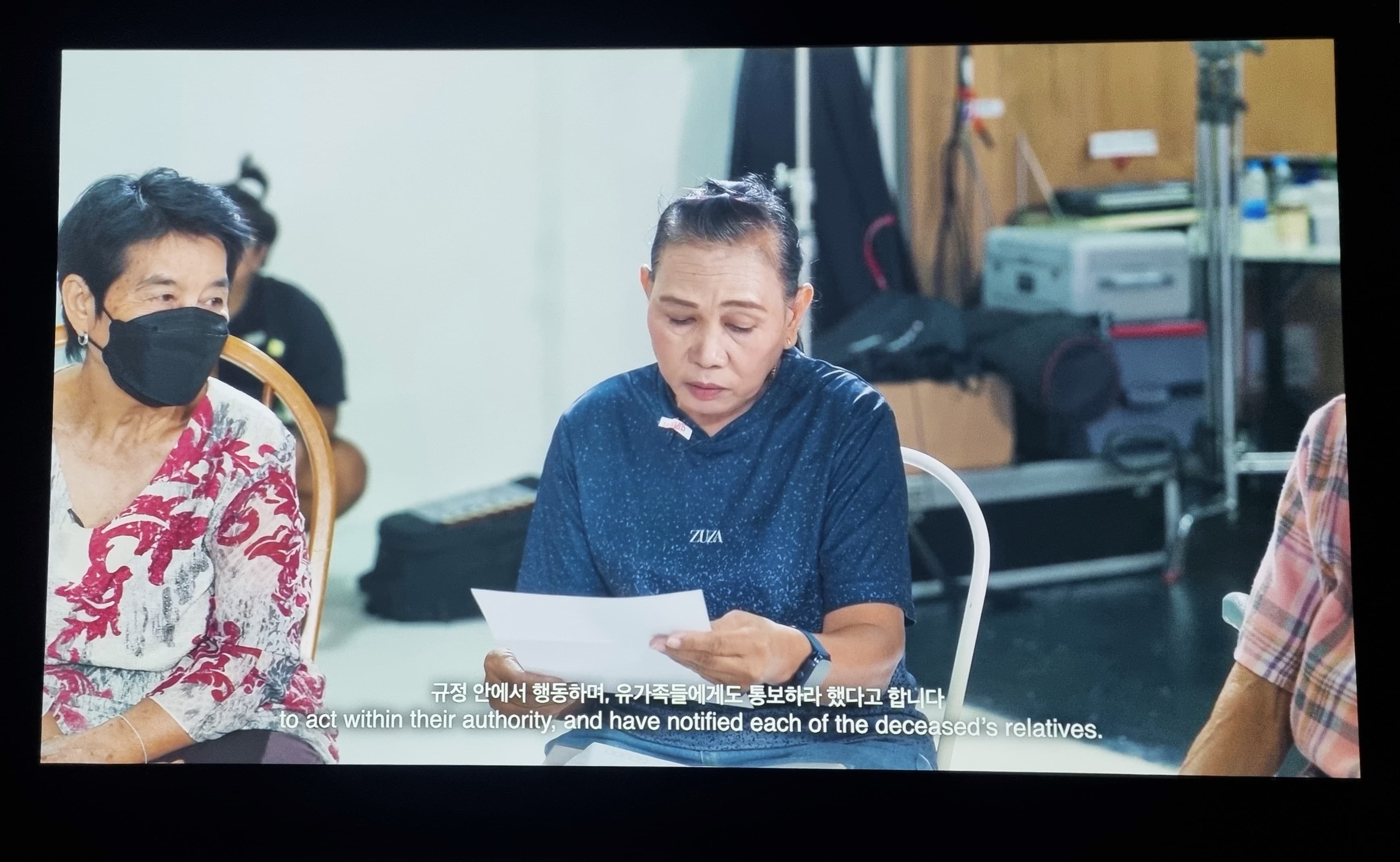

이러한 장치는 근과거를 언술하는 아노차 수위차콘퐁(Anocha Suwichakornpong, 1976~)의 작품 〈서사(Narrative)〉(2025)에서도 드러납니다. 영상 촬영을 위해 사람들을 모아 공동체가 겪어온 폭력과 삭제된 기억의 감각적 복원을 도모하는 이 작품은 2010년 방콕 반정부 시위 이후의 이야기를 소집단의 대화와 제스처로 소조합니다. 관객은 외부와 차단된 것처럼 보이는 세트장에 모인 출연자와 스태프의 반응만으로 15년 전부터 지속되어 온 팩션(faction)을 따라가게 됩니다. 방콕의 풍경과 관련 인물의 소지품, 기억을 구성하는 딸림 자료의 모습은 49분의 영상 후반부에서야 조금씩 드러납니다. 사회 문제에 관한 내부적 인식과 배경이 소거된 시공에서 구체화되는 과정은 역설적으로 태국의 불안정한 정치 상황과 대조됩니다. 작품은 예술가가 진술하려는 사건과 사회적 후퇴가 교착되면서 앞으로 가지도, 뒤로 물러서지도 못하는 ‘현실’을 감지하게 합니다. 동시에 작품은 왕권, 불교, 군부에 저항하면서도 때로 협력해 온 태국 미술인들의 복합적인 입장을 그저 침묵 속에서 바라보도록 하며, 태국이라는 전제 자체를 곱씹게 합니다. 전체적인 정보 전달을 지연시키는 것, 이로써 공동의 사유가 휘발되지 않도록 붙잡아두는 작가의 선택은 외부의 압력과 내부 독재, 종교와 사회가 교착된 다른 국가들의 예술과 함께 놓아볼 수 있는 복합적인 사례입니다.

이러한 장치는 근과거를 언술하는 아노차 수위차콘퐁(Anocha Suwichakornpong, 1976~)의 작품 〈서사(Narrative)〉(2025)에서도 드러납니다. 영상 촬영을 위해 사람들을 모아 공동체가 겪어온 폭력과 삭제된 기억의 감각적 복원을 도모하는 이 작품은 2010년 방콕 반정부 시위 이후의 이야기를 소집단의 대화와 제스처로 소조합니다. 관객은 외부와 차단된 것처럼 보이는 세트장에 모인 출연자와 스태프의 반응만으로 15년 전부터 지속되어 온 팩션(faction)을 따라가게 됩니다. 방콕의 풍경과 관련 인물의 소지품, 기억을 구성하는 딸림 자료의 모습은 49분의 영상 후반부에서야 조금씩 드러납니다. 사회 문제에 관한 내부적 인식과 배경이 소거된 시공에서 구체화되는 과정은 역설적으로 태국의 불안정한 정치 상황과 대조됩니다. 작품은 예술가가 진술하려는 사건과 사회적 후퇴가 교착되면서 앞으로 가지도, 뒤로 물러서지도 못하는 ‘현실’을 감지하게 합니다. 동시에 작품은 왕권, 불교, 군부에 저항하면서도 때로 협력해 온 태국 미술인들의 복합적인 입장을 그저 침묵 속에서 바라보도록 하며, 태국이라는 전제 자체를 곱씹게 합니다. 전체적인 정보 전달을 지연시키는 것, 이로써 공동의 사유가 휘발되지 않도록 붙잡아두는 작가의 선택은 외부의 압력과 내부 독재, 종교와 사회가 교착된 다른 국가들의 예술과 함께 놓아볼 수 있는 복합적인 사례입니다.

무빙이미지가 동시대 태국 미술의 특색을 글로써 풀어갈 실마리가 되어주었다면, 공동체적 영감을 건네는 또 다른 희소한 모델로는 우머니페스토(Womanifesto)를 꼽을 수 있겠습니다. 이는 민족적 구성뿐만 아니라 정치적 입장과 지역을 초월해 대안적인 국제적 연결망을 지속하는 동시에 과거의 자료를 현재에 뿌리내리는 역사적 실례로서 뜻깊습니다. 기득권과 남성 중심적인 남동아시아의 시공 속에서 자신의 미술살이를 나누고 ‘일반적’ 의제의 주변부로 상대화되어 온 공동의 곤경을 논의하는 배움의 장은 현재 우리가 채택해야 할 실천적 방식으로서도 유용합니다. 태국에 위치한 반 우머니페스토(Baan Womanifesto)의 지속은, 그러므로 앞서 반추한 태국의 또 다른 면모를 현시합니다. 쑨거의 언명처럼, 우리가 보편적이라 여기는 이론을 상대화하는 연습을 수행해야하는 세대로서, 대중적인 시각 요소보다 앞서 언급한 태국 작가들이 견지한 대안적 의제를 중시하며 미술을 독해할 때, 진정 아시아라는 사유 공간에 관한 다면적 이해와 역설적 면모가 합치될 수 있으리라 생각합니다.

이제 당신께 드리는 이 편지를 마무리하려 합니다. 남한과 다른 이웃 남동아시아 국가와 다른 탈식민적 궤적을 토대로 전략적 절충주의를 발전시켜 온, 태국이라는 사유 공간에서의 미술이 매개하는 아시아성에 관한 우리의 관찰에 대한 당신의 의견을 듣고 싶다는 바람과 함께요. 그럼으로써 검열과 집단행동을 비공식적으로 제재해 온 남동아시아의 미술 생산과 수용 갈래를 배수로 늘려가고 싶습니다. 지금까지 전해드린 4개월간의 이야기가 태국 미술에 관한 궁금증을 솟아오르게 하고, 보이지 않았던 정보와 감정에 더 가까이 갈 수 있는 단초가 되어주었기를 바랍니다. 그럼, 또 연락드릴게요.

서울에서, 현아와 혜인.

*이 편지의 바탕이 되어준 추가적인 읽기 목록입니다.

① 순턴푸. 『프라아파이마니』. 김영애 옮김. 서울: 지식을만드는지식, 2015.

② 씨부라파. 『그림의 이면』. 신근혜 옮김. 서울: 을유문화사, 2022.

③ 테, 데이비드. 「작가의 주권에 대하여」. 『이미지 소비시대의 황혼』. 서울: 국립현대미술관, 2019: 69-75.

④ Lara van Meeteren and Bart Wissink. What Should Biennials Do?. Bangkok: Poop Press, 2019.

⑤ Lenzi, Iola. “Beyond Local: Thailand’s Recent Art of Political and Historical Witness.” In Next Move: Contemporary Art from Thailand, 36–45. Singapore: Earl Lu Gallery, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, 2003.

⑥ Lenzi, Iola. “History and Memory in Thai Contemporary Art.” C-Arts (London), no. 11–12 (2009): 16–21.

⑦ Teh, David. "The Art of Interruption: Notes on the 5th Bangkok Experimental Film Festival." Theory, Culture & Society 25, no. 7–8 (December 2008): 309–320.

⑧ Teh, David. “Itinerant Cinema: The Social Surrealism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.” Third Text 25, no. 5 (2011): 595–609.

⑨ Teh, David, et al. Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai 1992–98. London: Afterall Books, 2018.

⑩ Asia Art Archive. Womanifesto Archive. Hong Kong: Asia Art Archive. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/womanifesto-archive

⑪ Womanifesto. Essays of Womanifesto – An International Art Exchange. https://www.womanifesto.com/essays/

AS는 2023년 조현아와 문혜인이 결성한 스터디 및 큐레토리얼 콜렉티브로, 서구 중심의 제도권 교육에서 누락되어 온 남동아시아 시각예술사를 재서술한다. 이를 위해 AS는 ‘남동’이라는 관점을 바탕으로 서구와 군부, 제도가 구축해온 서사를 우회하며, 남동아시아 시각예술을 읽기, 쓰기, 오역하기, 재생산하기 등 다양한 실천을 통해 탐구한다. 또한 근과거의 사회적 시각이 반영된 작품과 기록물을 살피는 프로젝트를 이어 오고 있다.

1 순턴푸, 프라아파이마니, 김영애 옮김 (서울: 지식을만드는지식, 2015). 83. 인어 낭응악과 결합하기 위해 프라아파이마니가 건넨 말로, “부부가 되는 것은 모든 동물에게 가능한 것”이라는 인식을 드러낸다. 이는 성별 구분이나 소수자성에 구애받지 않는 태국의 성 문화가 과거로부터 이어져왔음을 엿볼 수 있는 대목이기도 하지만, 필자는 해당 문장이 이득을 얻고자 타자 또는 타국과의 연합과 회유를 지속해온 태국 기득권의 되풀이되는 태도를 드러낸다고도 본다. 결국 낭응악은 “온전한 인간 모습을 한 사내애”를 낳았지만 프라아파이마니는 또 다른 인간 여성에게 구애하고, 이후 혼인한다.

2 일본은 태국의 필요에 의한 우호 관계를 이어온 국가이기에 감성적인 무대로서 묘사될 때가 있다. 씨부라파의 『그림의 이면』은 그 예 중 하나로, 1930년대 후반 태국의 정치적 전환과 구세력과 신세력을 대표하는 인물간 끌림과 결국 합치되지 못한 상황을 드러낸다. 태국 미술을 공부하는 과정에서 우리는 일본에서 유학한 젊은 태국인 남성을 화자로 내세운 소설이 태국 안에서 기념비적인 작품으로 남은 이유와, 태평양전쟁기 태국의 인식이 동시기 한국이나 인접 국가의 그것과 무엇이 달랐는지를 면밀히 살펴보고자 했다. 태국 청년이 일본에서 사랑한 경험을 바탕으로 자아와 사회적 위치를 확립해가는 내용은 1932년 시암 혁명을 통한 입헌군주제로의 전환과 여성으로 표상된, 외부 사회에 노출된 빈도가 적은 기존 세력과 고별하는 과정을 드러낸다고도 해석되어왔다. 『그림의 이면』은 동아시아뿐만 아니라 남동아시아 국가 안에서도 문화적으로 비균질적인 시각이 또렷하게 드러난다는 사실을 재고하는 계기가 되어주었으며, 시점의 차이를 여전히 발생시키는 예술로서 유효하다.

3 AS(문혜인, 조현아), 유승아의 대화 . 2025년 5월 25일.

4 태국의 영화 및 영상 작가들이 검열의 환경 안에서 사회비판적인 의식을 표하는 시도들과 불안정한 국가적 정치가 극명한 대비를 이루고 있다는 점에 관해 테는 다음과 같이 말했다. “영화의 경우, 이데올로기적 ‘정제’는 주로 배급 단계에서 이루어졌습니다. 여기에서 영화 제작자들은 시장 논리에 더 많이 노출된 덕분에 (아이러니하게도) 더 비순응적인 입장을 취할 여지가 있었던 셈입니다.” 2025년 9월 8일 조현아의 메일에 답신한 데이비드 테의 메일 내용 중 일부.

5 2008년 제5회 방콕실험영화제(Bangkok Experimental Film Festival) 《변화하는 것들이 많아질수록(The More Things Chang)…》의 큐레이터이기도 했던 데이비드 테는, 필자에게 현시점에서 35세 이하의 예술인 및 영화인이 처한 상황과 그의 세대가 취했던 정치적 입장차를 고려해 보라는 조언과 함께 연대의 형태와 세대별 단절의 문제를 언급했다. 또한 2016년 광주시립미술관에서 기획한 《아시아 민주·인권·평화미술전: 진실 비틀어 보기》에 참여한 군부 쿠데타를 지지하는 ‘진보적 미술인’ 수티 쿠나위차야논트(Sutee Kunavichayanont)에 관한 태국 민주주의문화운동가(Thai Cultural activist for Democracy, CAD)의 공개서한과 관련 논란을 지적하며 정치적 단절과 표면적인 연대의식에 비판적으로 접근해야 한다고 언급했다. “제가 그 나이였을 때, 제 또래는 정치에 손을 떼도 되는 분위기였어요. 정치적 무능의 악순환이 너무 뻔한 상황이었기 때문이죠. 당시에 유머, 추상, 혹은 “비정치적인” 척하는 예술을 선호하는 이들에 관한 비판적 시선은 거의 없었어요. 그렇더라도 주변부의 급진적 소수의 목소리에 불과했고, 그들은 예술에 관해서는 할 말이 적었죠. 하지만 요즘은 많이 달라졌어요. 태국의 진보적인 밀레니얼과Z세대가 느끼는 감정이 어떨지는 상상하기도 어려워요. 이들은 군주제 비판에 있어 훨씬 더 강경하고 직설적이에요. 저는 그 점을 높이 평가하지만, 동시에, 이들이 지난 세대 진보주의자들과는 더욱 단절되어 있다고 봐요. 저희 세대는 비판적이긴 했지만 머리로 하는, 때론 냉소적 접근을 했고 저희보다 앞선 세대는 스스로를 자유주의자라 칭하며 예술에 일정한 위상과 비판적 ‘자유’를 부여하려 했으나, 그들 중 많은 이들이 결국 군주주의자였죠. 이들은 1970년 세대의 ‘정신’을 계승하고 있다고 주장했지만, 제가 태국에 살던 2008년경 혹은 그 이전부터 그러한 계보가 허상임은 점점 명확해졌어요. 그래서 단절의 연속이 있는 셈입니다. 일종의 범국가적 정치 연대처럼 여겨진 ‘밀크티 연대’에 관한 환호가 있기도 했지만요. … 이런 단절을 알고 나니, 평소보다 더 조심스럽고 회의적인 입장을 취하게 됩니다. 어쩌면 다른 이들의 문제를 껴안는 것이, 아무리 바람직하다 하더라도, 이러한 세대 간 소외를 대변하는 건 아닐까요?” 2025년 9월 8일 조현아의 메일에 답신한 데이비드 테의 메일 내용 중 일부.

산마루에서 우리 만나요: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E Meet Us at the Ridge: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E (2024),

피스랜드 Peaceland (2024)

에킨 키 찰스, 〈산마루에서 우리 만나요: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E〉, 2024, 단채널 비디오, 컬러, 사운드, 8분 9초

* 이 작품은 카다잔두순(Kadazandusun) 전통 희생 제의, 몽구카스(Mongukas)를 기록한 장면이 포함되어 있습니다. 촬영 과정에서 현지 동물 보호 규정을 준수했습니다.

* 물소를 희생으로 바치는 과정에서의 혈흔 장면이 있습니다. 관람에 유의를 바랍니다.

에킨 키 찰스, 〈피스랜드〉, 2024, 단채널 비디오, 컬러, 사운드, 11분 31초

〈산마루에서 우리 만나요: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E〉와 〈피스랜드〉는 작가가 키마라강(Kimaragang) 부족의 구성원으로서 느끼는 복합적인 감정을 어린 두 소녀와 노년의 세 여성을 통해 드러낸 작업입니다. 〈산마루에서 우리 만나요〉에는 카다잔두순(Kadazandusun) 전통의 희생 제의인 몽구카스(Mongukas) 과정에서 도살 당하는 물소의 모습과 산등성이 곳곳을 자유롭게 누비는 소녀들이 교차합니다. 키마라강 사람들은 죽은 이의 영혼이 사후에 낙원인 키나발루산(좌표: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E)으로 향한다고 믿습니다. 그러나 이러한 전통의 믿음은 어린 소녀들에게 동경인 동시에 두려움의 대상이 됩니다. 〈피스랜드〉는 세 친구 레나, 미나, 조니가 한 달치 식료품을 장만하고, 고향을 떠난 레나의 딸을 만나기 위해 불법 트럭을 타고 도시로 향하는 여정을 담습니다. 장난스럽고 생기넘치며, 또 때로는 악동스러운 노년 여성의 모습을 담습니다. 호젓한 어린 소녀들과 호쾌한 할머니들, 어린 나와 미래의 나의 모습을 은유하는 이야기를 통해 작가는 관습과 전통, 규율의 개념을 단수형으로 축소시키지 않고 복수형으로 만듭니다.

Ekin Kee Charles, Meet Us at the Ridge: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E, 2024, single-channel video, color, sound, 8min. 9sec.* This work documents the traditional sacrificial ritual of the Kadazandusun people. During the filming process, local animal protection regulations were followed.

* This work contains sensitive content and scenes with blood. Viewer discretion is advised.

Ekin Kee Charles, Peaceland, 2024, single-channel video, color, sound, 11min. 31sec.

Through the figures of two young girls and three women in their sixties, the works Meet Us at the Ridge: 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E and Peaceland illustrate the complex emotions that artist Ekin Kee Charles experiences as a member of the Kimaragang people. The Kimaragang believe that the souls of the dead face in the direction of Mount Kinabalu (located at 6.0753° N, 116.5588° E), which represents paradise in the afterworld. For the young girls, however, the traditional beliefs of the Kadazan-Dusun are objects of both admiration and fear. The video work juxtaposes the slaughter of water buffaloes and images of girls traveling freely through the mountain ridges with the experience of fear in the depths of a river. The result resembles the way in which life makes a leap forward at the moment of death, fusing and flowing into death in the process. In Peaceland, three friends named Rena, Mina, and Joni buy a month’s worth of food and board an illegal truck on a journey to the city to see Rena’s daughter, who has left her hometown. The elderly women appear playful, vibrant, and sometimes mischievous. Through stories featuring quiet young girls and animated seniors, artist Ekin Kee Charles offers metaphorical representations of her own younger and future selves. In the process, she transforms conventions, traditions, and norms into something plural rather than reducing them to a singular level.

에킨 키 찰스는 카다잔두순 다약(Kadazandusun Dayak) 계통 아래에 속하는 소부족, 키마라강(Kimaragang)족의 후손이다. 에킨은 산악 내륙 지역에서 코타 마루두(Kota Marudu)로 이주해온 가족들이 모여 사는 폐쇄적인 공동체 속에서 성장했다. 에킨의 시각적 표현은 늘 세상을 경이롭게 바라보는 어린 아이와 같은 마음가짐의 시선에서 출발한다. 《Among Us》(타이베이 현대미술관, 2025)에서 개인전을 개최하였으며, 제40회 베를린 인터필름 국제단편영화제(2025), 씨쇼츠 영화제(2025) 등에서 작품을 상영했다.

Ekin Kee Charles is an indigenous filmmaker from Sabah, Malaysia. She is a descendant of the Kimaragang tribe, a sub-tribe from the Kadazandusun Dayak umbrella. Ekin grew up in a closed community that consisted of family members who migrated from the inland mountain area to Kota Marudu, Sabah. Almost instinctively, her visuals often come from an innocent perspective, one that still sees the world with wonder. Ekin Kee Charles held a solo exhibition, Among Us (Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, 2025), and her works have been screened at the 40th Interfilm Berlin International Short Film Festival(2025), the SeaShorts Film Festival(2025).

좀 더 나은 세상을 만드는 법 Cải tiến Thế giới (How to Improve the World) (2021)

응우옌 트린 티, 〈좀 더 나은 세상을 만드는 법〉, 2021, 단채널 비디오, 흑백, 컬러, 사운드, 47분

소리와 이미지 가운데, 이미지를 신뢰한다는 응우옌의 딸과 소리를 믿는다는 토착 공동체의 한 남성. 〈좀 더 나은 세상을 만드는 법〉은 베트남 중앙고원 지역 토착 공동체의 한 남성을 따라, 청각 중심의 문화에서 기억을 만드는 방식을 관찰합니다. 이는 시각을 중심으로 두고 있는 세계와 조금 다릅니다. 응우옌은 말합니다. “세계화되고 서구화된 문화가 시각 매체에 장악되면서, 나는 영화 창작자로서 시각 이미지가 가진 서사적 권력을 저항해야 한다는 필요와 책임을 느낍니다. 그래서 세계를 감각하는 보다 균형적이고 섬세한 접근—특히 청각적 풍경에 주의를 기울이는 방식—을 찾고자 합니다. 그것은 제가 늘 관심을 가져온 ‘알 수 없는 것, 보이지 않는 것, 접근 불가능한 것, 그리고 가능성들’과도 맞닿아 있습니다.”

Nguyễn Trinh Thi, Cải tiến Thế giới (How to Improve the World), 2021, single-channel video, B&W, color, sound, 47min.

Nguyễn’s daughter trusts more in images than in sounds, while another member of the indigenous community says that he trusts more in sounds. Cải tiến Thế giới (How to Improve the World) follows a man living in an indigenous community in Vietnam’s Central Highlands as it observes how memories are formed in a hearing-centered culture. The result appears somewhat different from a world that focuses on sight. Nguyễn says, “As our globalised and westernised cultures have come to be dominated by visual media, I feel the need and responsibility as a filmmaker to resist this narrative power of the visual imagery, and look for a more balanced and sensitive approach in perceiving the world by paying more attention to aural landscapes, in line with my interests in the unknown, the invisible, the inaccessible, and in potentialities.”

응우옌 트린 티는 기억의 문제를 매개로 감춰지거나 밀려나고 오해된 역사를 탐구하는 동시에 베트남 사회에서 예술가가 놓인 위치를 비평적으로 성찰해 왔다. 최근에는 소리와 ‘듣기’의 힘에 주목하며, 이미지, 사운드, 공간의 복합적인 관계성을 탐구하고 있다. 도큐멘타 15(2022), 브리즈번 아시아 퍼시픽 현대미술 트리엔날레(2019), 시드니 비엔날레(2018), 리옹 비엔날레(2015), 후쿠오카 아시아 미술 트리엔날레(2014) 등 단체전에 참여했다.

Nguyễn Trinh Thi centers on the question of memory, through which she critically examines hidden, displaced, and misinterpreted histories, as well as the position of artists within Vietnamese society. In recent years, her practice has expanded to explore the power of sound and listening, and the multilayered relationships between image, sound, and space. Her works have been presented in major international exhibitions and film festivals, including documenta 15(2022), the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art(2019), the 21st Biennale of Sydney(2018), Lyon Biennale(2015), Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale(2014).

굿키친의 커르자 바크티: 협업, 혼돈, 통제, 갈등, 그리고 돌봄을 요리하는 장소 Kerja Bakti in Gudkitchen: A Place to Cook Collaboration, Chaos, Control, Conflict, and Care

커르자 바크티(Kerja Bakti)란 무엇이며, 어떻게 번역될 수 있을까? 인도네시아어 커르자 바크티는 kerja(노동)와 bakti(봉사)가 결합된 표현으로, 일본어 勤労奉仕(kinrōhōshi, 킨로호시, ‘공공노동’ 혹은 문자 그대로 ‘노동 봉사’)에서 유래한 용어다. 이 표현은 여러 층위의 의미를 지닌다. 지역사회 봉사나 자원봉사뿐 아니라, 금전적 보상이 없는 노동까지도 포함될 수 있다. 위나휴 아다 유니야티(Winahyu Adha Yuniyati)는 “커르자 바크티는 사람들이 함께 일하며 특정한 목표를 달성할 때”1라고 정의한다. 브릴 사전(Brill Lexicon)에서는 이를 “지역사회나 국가의 이익을 위해 농민들이 수행하는 의무적 공동노동”2 으로 설명하고 있다. 보웬(Bowen)은 “의무적 노동 봉사, 즉 kerja bakti(문자 그대로 ‘자발적 봉사노동’)라고도 불린다”3 고 언급한다. 아구스 수위그뇨(Agus Suwignyo)는 커르자 바크티를 고통 로용(gotong royong)의 맥락 속에 위치시키며, 이를 “경제적·사회적 회복력을 강화하기 위해 이웃 간에 발휘되는 공동체 정신”4 이라고 설명한다.

나는 커르자 바크티를 교과서를 통해 배우기보다는, 토요일 아침마다 이웃들이 빗자루와 걸레, 손수레를 들고 나와 거리와 도랑을 청소하던 풍경을 통해 배우며 성장했다. 학교에서는 수업이 끝난 뒤 모두가 남아 바닥을 문지르고 책상을 닦는 일을 의미했다. 자바 본토에서 멀리 떨어진 수마트라의 메단에서도 이 단어가 쓰였는데, 이는 특정 자바어 표현들이 국가 정책의 수단으로 자주 사용되던 수하르토 시대의 유산으로 보인다.

나는 내가 속한 굿스쿨(Gudskul)이 운영하는 이동형 프로젝트, 굿키친의 관계 속에서 커르자 바크티를 떠올리게 되었다. 굿키친은 자카르타, 도큐멘타 15(documenta fifteen)의 룸붕 원(lumbung one), 텐트하우스(Tenthaus)가 기획한 모멘텀 12(MOMENTUM 12), 그리고 파리(Pari)와 아랍 시어터 스튜디오(Arab Theatre Studio)와 함께한 웨스턴 시드니의 룸붕에서 각기 다른 맥락으로 선보여 졌다. 나는 커르자 바크티가 점점 층위를 더하며 정치화되고, 마모되고 있다는 점을 곱씹으면서도, 여전히 그것이 유효한 개념이라고 느낀다.

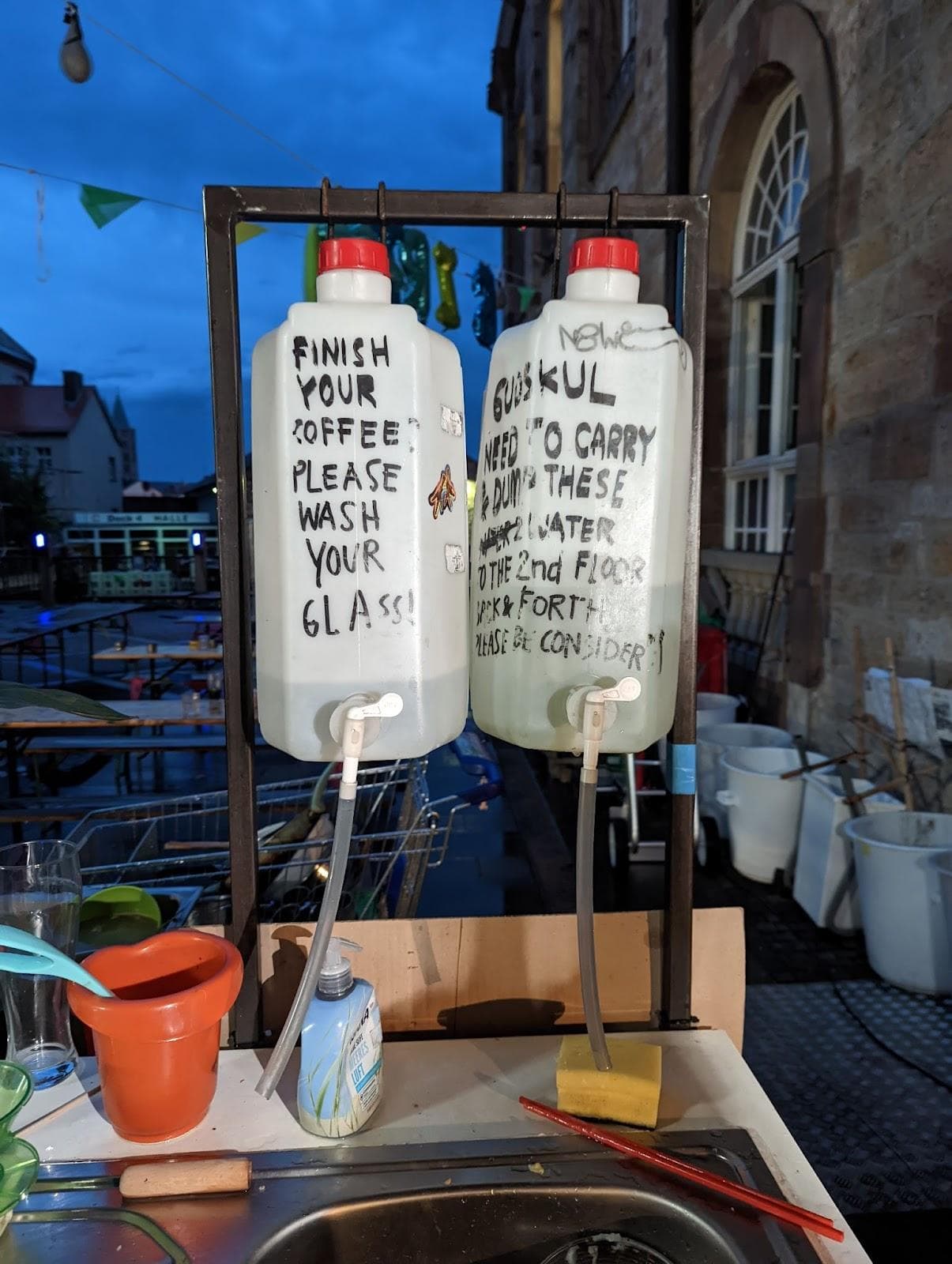

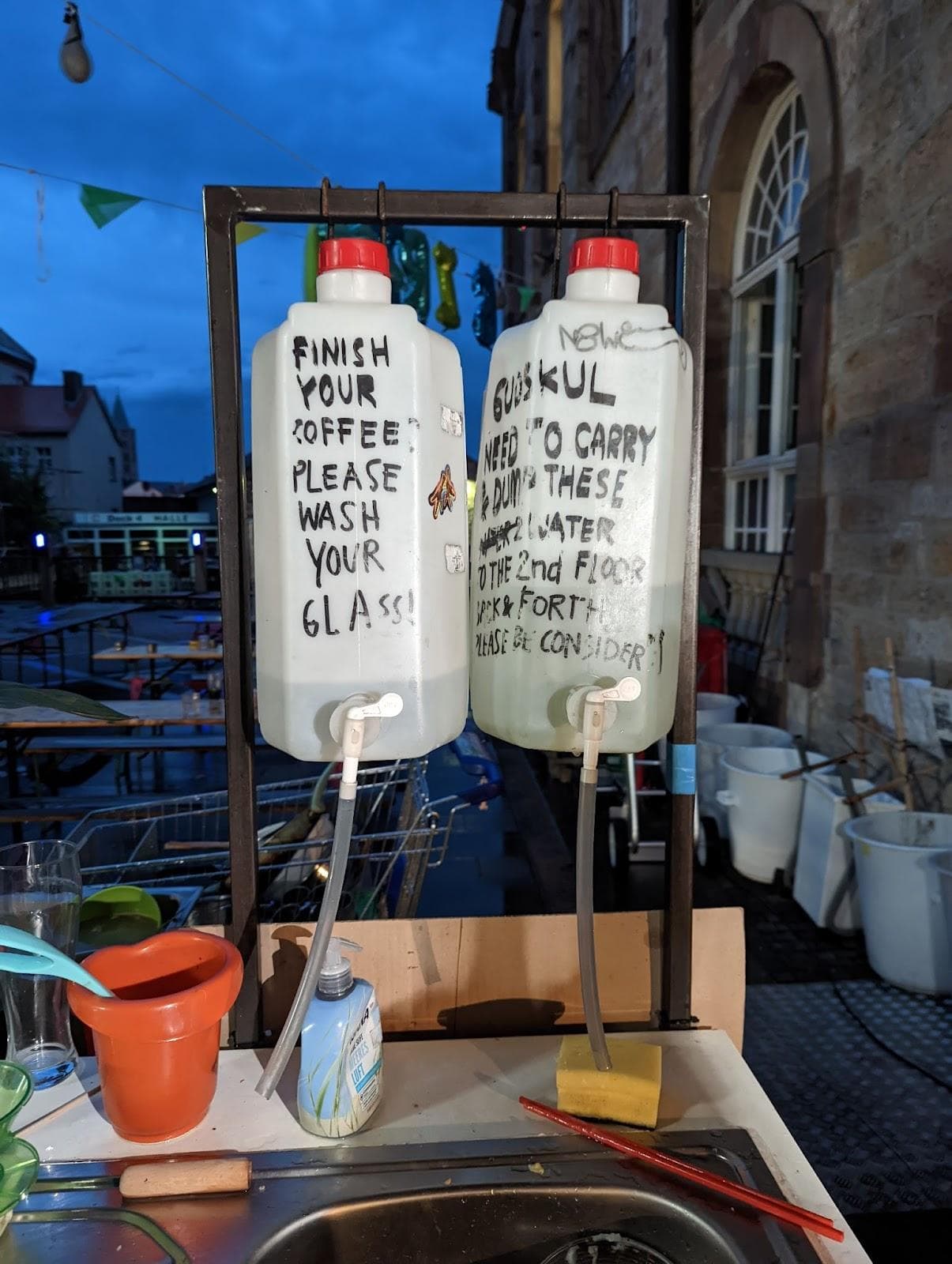

작업이 커르자 바크티의 계기가 될 때, 어떤 일이 일어날까? 굿키친 또한 동네 청소와 마찬가지로 제대로 작동하기 위해서는 협력이 필요했다. 배관은 손으로 관리해야 했고, 물은 손수레로 옮겨야 했으며, 예기치 않게 100명의 참가자가 몰린 가라오케 행사가 끝난 뒤에는 수십 개의 접시를 모두 씻어야 했다.

굿스쿨 『하비스트 북』(Gudskul Harvest Book, 2022)은 굿키친을 다음과 같이 설명한다.

“굿키친은 우리가 돌봄을 받고, 다시 힘을 얻는 장소였다. 낮이든 밤이든 언제나 누군가가 요리를 하고, 청소를 하며, 재료를 손질하고, 이야기를 나누고, 수다를 떨고, 지식을 나누고, 음악을 연주하며, 함께 춤추고 노래했다.”

노동은 끊임없이 이어졌고, 때로는 눈에 띄지 않았으며, 언제나 낭만적이지 않았다. 피켓(piket), 즉 청소를 담당자는 상호 책임을 실천하는 하나의 관습이 되었다. 설거지 책임을 두고 생겨난 눈치싸움은 단순히 위생의 문제가 아니라 공정성의 문제와도 맞닿아 있었다. 방문객들 중 일부는 주방을 식당처럼 여기며, 더러운 접시를 ‘보이지 않는 노동자’가 치워주기를 기대했다. 이러한 상황은 공동의 노동을 바라보는 서로 다른 문화적 가치관을 드러냈다.

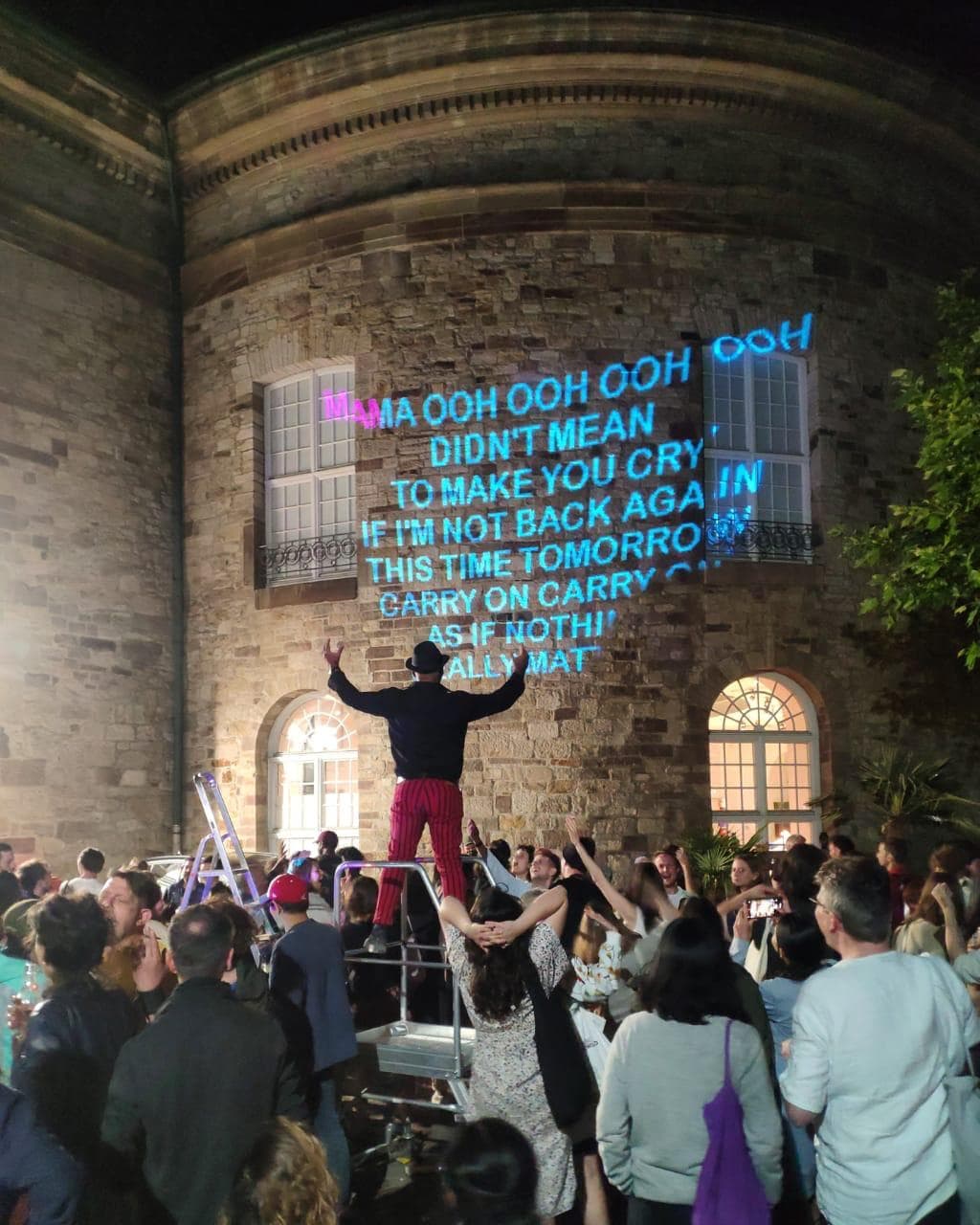

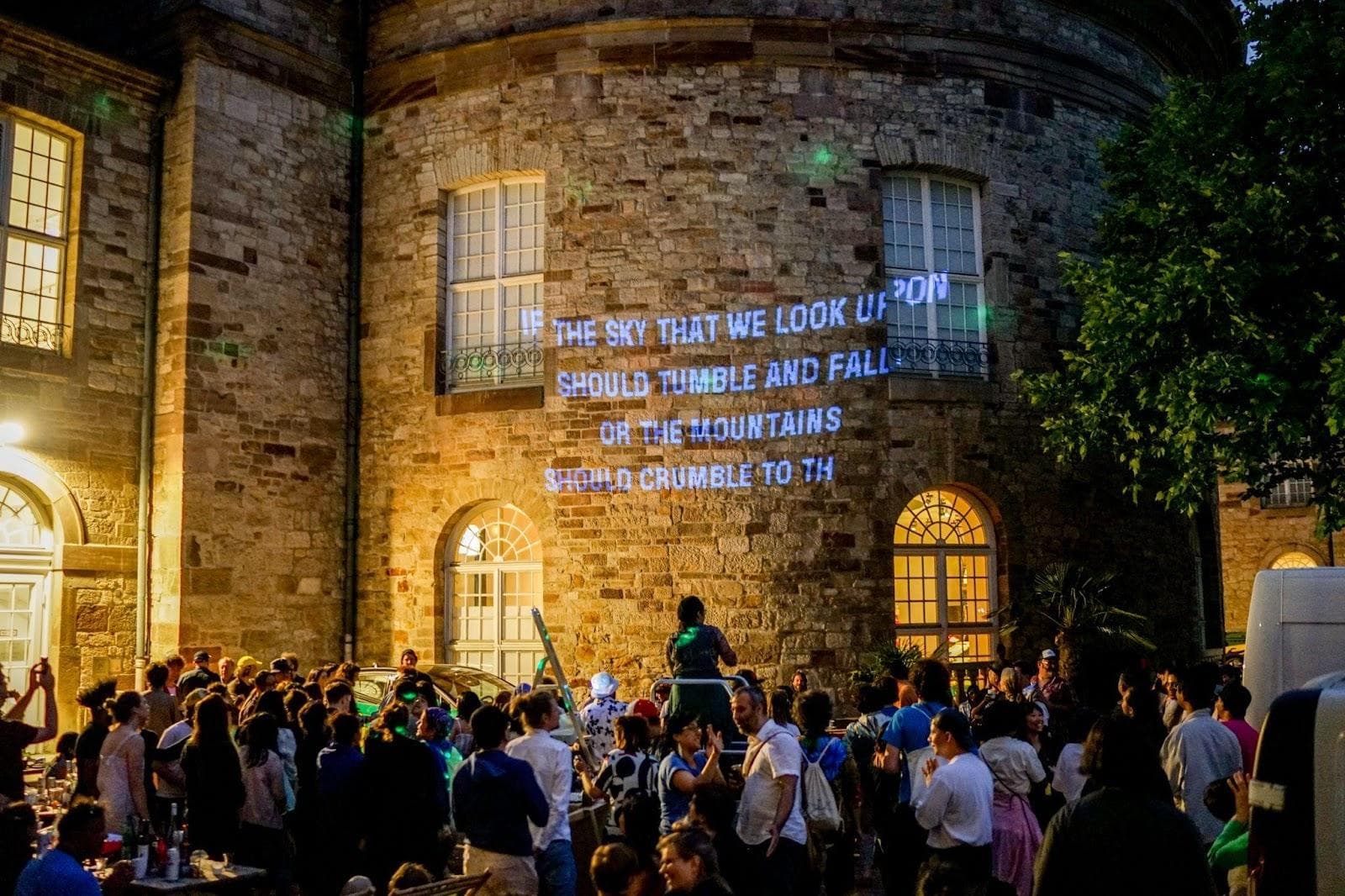

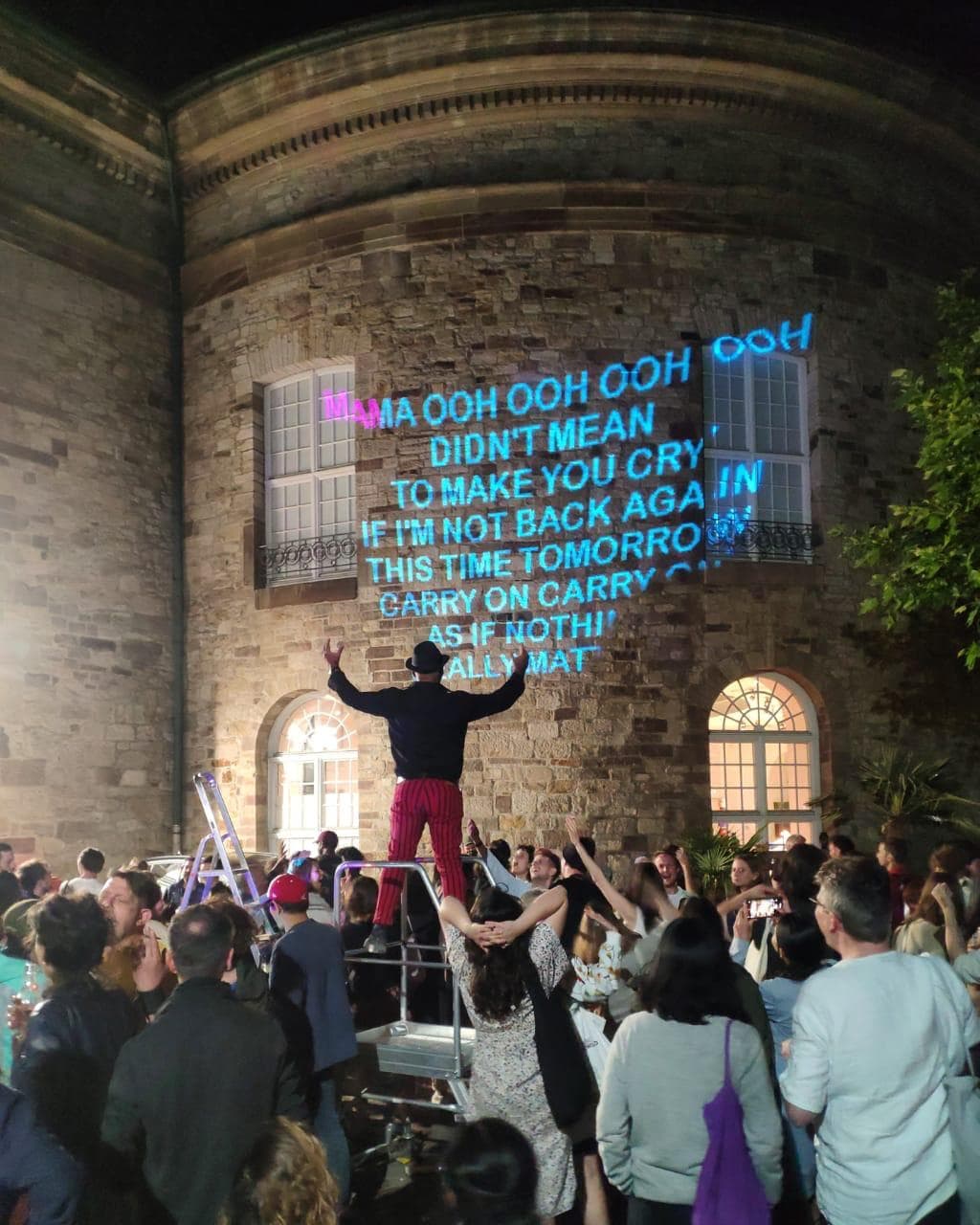

룸붕 원과 모멘텀 12에서는 전시장 내부에 기숙사와 거실이 설치되어, 전시 공간이 공동 거주의 장소로 변모했다. 아티스트, 협업자, 방문객들은 함께 자고, 먹고, 토론했다. 전통적인 전시가 관객을 예술적 노동으로부터 분리시키는 것과 달리, 이 공간에서는 갈등과 돌봄이 불가분하게 얽혀 있었다. 하루는 한 예술가가 준비한 인도네시아 음식을 운영자와 기자들이 함께 나누는 점심으로 시작되거나, 목판화 워크숍으로 이어졌다. 이어 정치적 주제로 티타임 토론이 열리기도 했고, 그 사이 몇몇 아티스트가 즉흥적으로 부엌에서 인도네시아 전통 타악기인 타블라를 연주하며 모두의 주의를 흐트러뜨렸다. 이후 새벽 3시까지 모두 함께 취한 채 퀸의 노래를 부르며 가라오케에 온 것처럼 즐겼고, 마지막에는 이곳저곳에 숨겨진 맥주병을 모두가 다함께 치우며 하루를 마무리하곤 했다. 이러한 활동들은 단순하거나 부수적인 일이 아니라, 프로젝트의 핵심이었다. 여기서 ‘예술’이란 마찰을 통해 맺어진 우정이었다. 공동 노동에서 비롯된 피로, 즉흥적인 식사에서 느껴지는 즐거움, 문화적 오해에서 생겨난 불편함. 이 모든 경험이 곧 예술이었다.

헙업의 숨은 대가

집단에서, 협업에 대한 공적인 약속은 종종 그 이면의 사적 비용을 감춘다. 그것은 바로 협업을 가능하게 하는 과정에서 발생하는 정신적, 정서적 부담이다. 미술의 맥락에서 ‘미술가’는 대체로 주인공처럼 여겨지고, 그들의 작품은 눈에 띄는 결과물로 남아 찬사를 받지만, 돌봄과 조율로 이루어진 기반의 구조는 보이지 않는 영역으로 사라진다. 커르자 바크티의 경우와 마찬가지로, 이러한 노동은 명목상으로는 ‘자발적’일지라도 실제로는 의무처럼 수행된다.

사회적 규모에서의 예술은 삶과 관계를 조직하고 이끌어가는 하나의 사회적 구조다.5 어떻게 살아가고, 어떻게 보고, 어떻게 연결될 것인가에 관한 제안들로 이루어진다. 그러나 이러한 제안들은 여러 층위의 감정노동을 요구한다. 즉각적인 관리 조치, 감정의 중재, 함께 식사를 하는 일, 말없이 이뤄지는 화해 같은 순간들. 이러한 노동은 결과 보고서나 전시 벽면에 기재된 크레딧에 깔끔하게 담기지 않는다. 오히려 기억과 소문으로 남는다. 축제가 끝난 뒤의 탈진, 나누어지지 않은 공로에 대한 서운함, 너무 서둘러 내려진 결정에 대한 후회. 우리 삶에서 벌어지는 온갖 얽힘과 다르지 않은 이야기들이다.